How ‘Moneyball’ and ‘Sugar’ Altered the Baseball Movie

From “Eight Men Out” to “Field of Dreams,” baseball movies are usually enraptured by the past. Steeped in traditions, these films celebrate homespun heroes whose anything-is-possible journeys toward a championship elevate our spirits. But two baseball movies from the last 20 years had something else on their minds that would alter how the sport was looked at onscreen. Bennett Miller’s “Moneyball” (2011), based on a true story, and Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck’s “Sugar” (2008), aren’t about tenacious winners or mythic achievements. Instead, they’re fascinated by failure and community.

That notable shift defies a subgenre built on uplift. A baseball movie will often spin a yarn about a band of misfits coming together for an unlikely title run (“Angels in the Outfield”). They can also center once-talented players given one more chance at greatness (“The Natural”), or recall life-changing summers (“The Sandlot”). They tout the majesty, poetry, superstitions and purity of the sport, appealing to truisms lodged in our cultural understanding of fairness: three strikes, you’re out and, as Yogi Berra said, “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Following the Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), “Moneyball” aims to critique an unfair system not by yearning for the past, but by deconstructing the present. Beane is an executive whose small market ball club can no longer compete monetarily with big spenders like the New York Yankees, so he hires the nerdy Yale economics graduate Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) and turns to the teachings of Bill James, a writer who preached sabermetrics as a statistically informed way to maximize talent. Beane and Brand’s unorthodox approach puts them in opposition to the team’s irritable old school manager (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and the craggy scouts who rely on their ingrained biases to evaluate players.

While Beane deconstructs the business of baseball, assembling a stacked roster of discarded players, “Moneyball” the movie also disassembles the subgenre by not really being about baseball. Partway through the film, Steven Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin’s patient screenplay introduces Beane’s young daughter, who hopes the team wins enough for her dad to keep his job. Pitt is wonderful in these scenes, softening Beane’s rigid executive exterior for a kinder, sweeter approach that slowly builds the importance of this father-daughter relationship to the point of Beane turning down a higher paid position with the Boston Red Sox (coincidentally, the A’s are leaving California in 2028 for a lucrative offer to play in Las Vegas).

Seeing Beane’s embrace of fatherhood recalls an imperative moment in Ken Burns’s “Baseball.” In that documentary mini-series, Mario Cuomo, the former New York governor, describes baseball as a “community activity,” in which “you find your own good in the good of the whole.” As much as Beane prizes winning in “Moneyball,” his journey becomes about cherishing family.

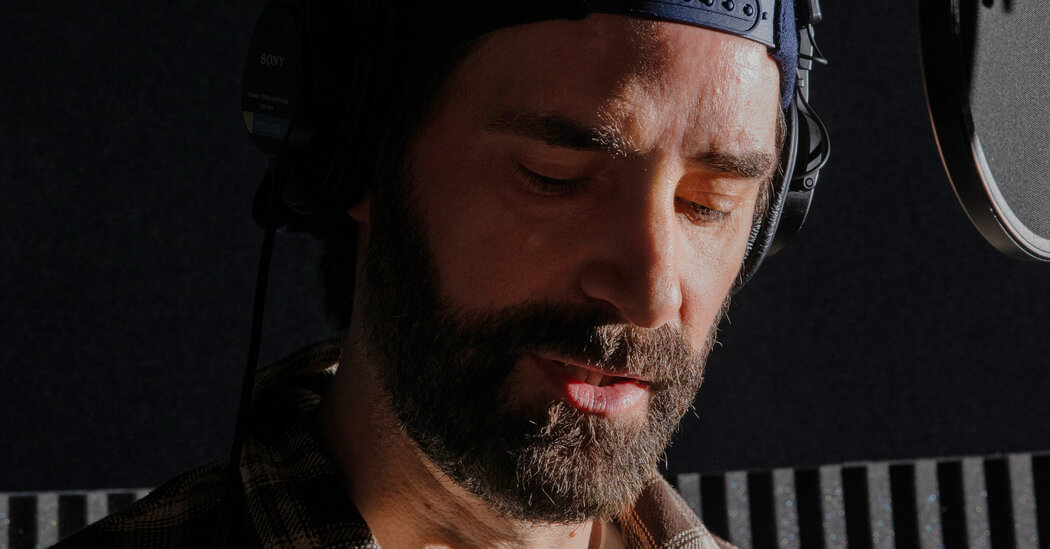

Miguel Santos, a.k.a. Sugar, the fast-rising pitcher at the heart of Fleck and Boden’s hardscrabble film, also learns about the power of community. Hailing from San Pedro de Macorís, the 19-year-old Sugar (Algenis Perez Soto) pitches for the fictional Kansas City Knights baseball academy where he hopes to earn life-changing money for his family in the major leagues.

Like Beane in “Moneyball,” Sugar is working against a broken system. Players like Sugar who aren’t from Canada, the United States or a U.S. territory aren’t eligible for the draft. Instead, they’re acquired through an individual team’s international pool money. This system is meant to give smaller teams like the A’s the ability to compete against bigger franchises for cost-controlled talent, but ultimately limits these athletes’ earning potential. Earlier this year, for instance, the Japanese prospect Roki Sasaki signed with the Dodgers for $6.5 million, while last year, the Guardians’ Travis Bazzana, the No. 1 overall pick in the MLB draft, signed for $8.95 million.

Most players in the Dominican Republic, however, are like Sugar, who signs for $150,000, only to see a fraction of it after paying his agent. These athletes are often sent at a young age to train at baseball academies to begin their long path to the United States.

At first, “Sugar” is about the exploitation of Latino ballplayers on this journey. After wowing coaches, Sugar is assigned to a single-A team in Iowa. There, he lives with an older white couple who mostly exoticize him, and he falls for a religious white woman intent on proselytizing him. Because Sugar’s English is limited (the academy only taught him baseball words like “home run”), his camaraderie with other athletes of color is imperative. When he loses the community he’s built, leaving him isolated and disillusioned with the American dream, he quits baseball and escapes to New York City in the hopes of again finding solidarity.

Despite their disparate economic backgrounds, the protagonists in “Sugar” and “Moneyball” are linked by their setbacks. At 18 years old, Beane, a prized high school prospect, turned down a scholarship to Stanford for a mega baseball contract. Like Sugar, Beane both washes out of baseball and stops dreaming of wealth. “I made one decision in my life based on money, and I swore I’d never do it again,”Beane explains. The two characters instead rekindle their love of the sport by making families. Beane embraces his daughter, whose cover of Lenka’s “Just Enjoy the Show” inspires his growth. Sugar begins playing pick-up games in the park with other Latino former ballplayers.

These two films, with their stories grounded in human struggle, provided a blueprint for other newer sports movies like the basketball-minded “The Way Back” (2020), Rachel Morrison’s boxing character study “The Fire Inside” (2024) and Carson Lund’s beer league requiem “Eephus” (in theaters) to approach, with complexity, topics like alcoholism, poverty and aging. “Moneyball” and “Sugar” showed that baseball movies could do more than, as James Earl Jones says in “Field of Dreams,” “mark the time.” They could look over the fence into the anxieties of the soul.

“Moneyball” and “Sugar” are available on demand on most major platforms.