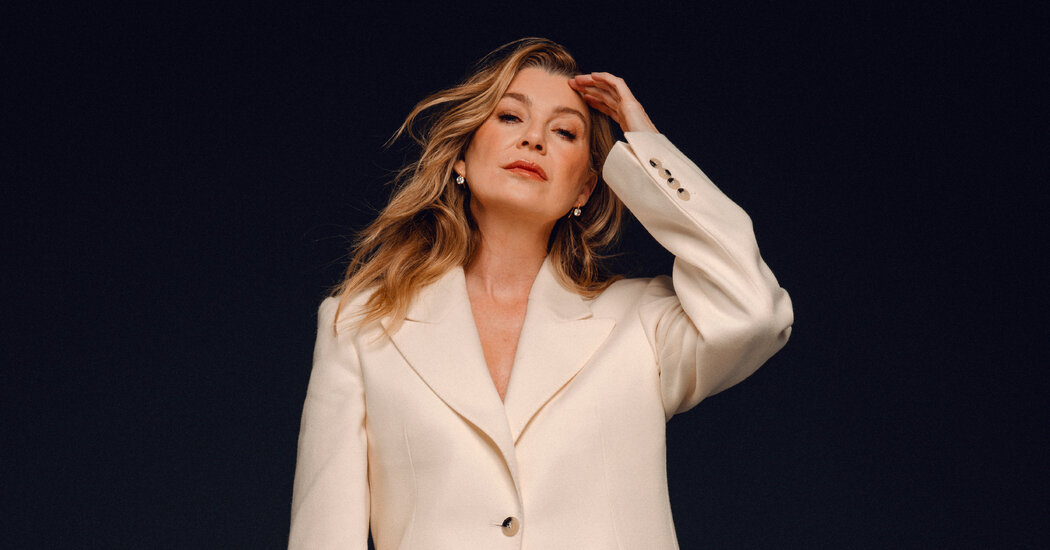

In ‘Good American Family,’ Ellen Pompeo Leaves the Hospital

At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ellen Pompeo stood in a room of Picassos, mostly in the Cubist style. She paused in front of a portrait of a woman in a blue dress. The eyes were at strange angles, the mouth tucked to one side. The nose was somehow everywhere.

Pompeo, 55, tilted her head, trying to resolve the features into one coherent face. Then she gave up.

“There’s three sides to every story,” she said. “Or six sides. Or nine. That is why art keeps us alive: Because everybody gets to see things their way, to make sense of them.”

For a long time Pompeo’s Hollywood story has been a simple one, the perspective fixed. She modeled sporadically throughout her 20s, had a starring role in one film and smaller parts in others. Since 2005 she has led the most popular medical show of the post-“ER” era, ABC’s “Grey’s Anatomy.” Pompeo plays the surgeon Meredith Grey, a sturdy moral center in a fervid, ethically uncertain world.

In the intervening years, barring a handful of crossover episodes on “Station 19,” a “Grey’s” sister show, Pompeo has amassed few other credits — a “Doc McStuffins” voice-over here, an appearance in a Taylor Swift video there. It wasn’t that she lacked artistic ambitions, but the “Grey’s” schedule was punishing and spending her brief hiatus making movies felt irresponsible, especially after she became a mother. (She and her husband, Chris Ivery, a music producer, have three children.)

In 2022, she renegotiated her “Grey’s” contract, reducing the number of episodes she would appear in. This allowed for her first new substantive role in nearly two decades, as a flawed suburban supermom named Kristine Barnett, in “Good American Family,” a limited series that premieres on Hulu on Wednesday.

Based on the real case of an adoption gone very wrong, “Good American Family” is told from multiple perspectives. In some, Kristine is the wronged, imperiled victim. In others, she is the villain. As with a Picasso, the viewer is left to make sense of it all.

While Pompeo waits for the show to debut and anticipates the 20th anniversary of “Grey’s Anatomy,” on March 27, she is reckoning with the picture of her own career — the choices she has made, the reasons for those choices. Having played one role for so long, she knows that her fans may resist seeing her in anything but scrubs. Still, she felt she had to try on something new.

“I’ve been dying for something else to do for years,” she said. “I’ve always wanted another opportunity. I finally have it. Yes, it’s scary. It might be the craziest, dumbest thing. But I’m going to trust in the universe.”

Pompeo, who had suggested the LACMA outing, arrived at the museum in the early afternoon, dressed in California mom chic — a trench coat over a sweatshirt and corduroy pants, with corduroy sneakers to match. Her lips were slick with a Rhode balm that Hailey Bieber personally sends her.

On that January day, the wildfires were still burning and the air quality was dire, though Pompeo’s Malibu home had survived the worst of it. “For now,” she said stoically.

In person, Pompeo is sharp, sardonic, coolly wise. She is a woman who knows her own worth and expects others to know it, too.

She has a reputation, entirely deserved, for brass and spunk and candor. Katie Robbins (“Sunny”), the showrunner of “Good American Family,” described her as a “salty, salty, salty broad.” Mark Duplass, her co-star on the show, called her “a badass Boston bitch in all the right ways.” Shonda Rhimes, the creator of “Grey’s Anatomy” and many other shows, complimented “an underbelly of toughness to her, which works well with how warm she is.”

If Pompeo is a tough cookie, she is also a surprisingly philosophical one. When she was 4, her mother died of an accidental overdose of prescription painkillers. So while she spends a fair amount of time thinking about why her life has worked out the way it has, she does not often question it.

“It’s my fate,” she said repeatedly during our conversation. “It’s my fate.”

This fate was not especially predictable. Growing up in a working-class Boston suburb, Pompeo didn’t have much exposure to the arts, though she loved movies — especially the Michelle Pfeiffer canon — and the aunt that she is named for brought her to see Broadway musicals. After high school, she followed friends to Miami and worked in bars. Offers of modeling took her to New York, though she knew she wasn’t destined to model. She was too short, too mouthy.

“I had too much to say and too many opinions,” she said. So she gave acting a try.

Soon she booked a sassy L’Oreal commercial, which brought her to the attention of casting directors and agents. Her first major role, in 2002, was in Brad Silberling’s weepie “Moonlight Mile.” Her reviews were strong, but the film underperformed.

“Which was the best thing that never happened because I probably would have been a complete [expletive],” she said. There were other roles, a few substantial (2003’s “Old School”), but editing whittled others away to nothing.

Offered television pilots, she passed on them — she wanted to be a movie star not a TV actress. But a couple of years after “Moonlight Mile,” she was broke. Her agent encouraged her to make the pilot for “Grey’s Anatomy” so that she could make her rent. Pilots almost never get picked up, he told her.

And then this one was. “There’s your fate,” Pompeo told me.

For Rhimes, it also seemed like fate. Imagining an actress for Meredith, she asked her casting director to find her someone like the girl in “Moonlight Mile.” The casting director told her she could have the girl in “Moonlight Mile.”

“There was a spirit about her,” Rhimes said. “There’s a quality about her that welcomes you in.”

“Grey’s,” in turn, was almost too welcoming. The money was good, especially after the first season, when Pompeo stood up for herself and renegotiated her contract.

“I gradually learned through other women teaching me, Shonda Rhimes telling me, to ask for what I deserve,” she said.

While the hours were long, they were regular, and the show shot in Los Angeles, where she lived. Gradually, she gave up her movie dreams. Then she gave up hoping for an Emmy, even though she thinks she should have been nominated for a couple. “But it wasn’t my fate,” she said.

Her feelings about her work on “Grey’s” are mixed. “Some seasons I was so ready and drastically excited and motivated. Other seasons, I was like, How am I going to get through this?” she said. She seems to have kept this exhaustion from her colleagues.

“I enjoy seeing her get giddy about things and to have a good time and to look for ways to have fun,” said Chandra Wilson, another original cast member.

A decade in, Pompeo no longer found the show creatively fulfilling. “No, not at all,” she said. She founded a production company, Calamity Jane, but failed to sell the projects she developed. She began to believe that she would never have another role.

After the pandemic lockdowns, she wondered if it might not be better to have no role at all. Financially secure but creatively frustrated, she thought about quitting “Grey’s” altogether.

“I couldn’t keep going,” she said. But she also couldn’t picture the show going on without her.

Dana Walden, who was then the chairwoman for entertainment at Walt Disney Television, heard her out. She allowed Pompeo to reduce her episodes by more than half. And she suggested that a show coming to Hulu, a Disney subsidiary, would be perfect for her: “Good American Family.”

The series is inspired by the real-life case of a Midwestern couple who adopted a girl with a rare form of dwarfism and then left her on her own. At first, Pompeo wasn’t sold on “Good American Family,” which hovers somewhere between fact and fiction as it offers multiple perspectives. (A hefty disclaimer at the start of each episode describes it as reflecting and dramatizing conflicting points of view rather than arguing for a definitive truth.)

She has little appetite for true crime and worried that the story might come across as “a little tabloid-y,” she said. And she didn’t want to play a character who in some versions of the narrative mistreats a child. What if her own children saw the show?

But her agent convinced her. Kristine was so different from Meredith that it would show audiences, instantly, that Pompeo was a real actress, not just a familiar face in blue scrubs.

Yet that familiarity is a useful tool. It helps viewers to side with Kristine, at least at first.

“We benefit from people coming in with a great love for her,” Robbins, the showrunner, said. “We needed someone who you trusted, who you believed in and wanted to root for, who you felt like aligned with.” Pompeo had that.

Duplass, whose family is obsessed with “Grey’s Anatomy,” saw it, too.

“What a beautiful weapon,” he said. “She knows the trust that audiences have in her, and she wields it carefully for a character who’s much more morally dubious.”

Pompeo’s approach to the role was similar to what she does on “Grey’s”: She tried to find the truth in each scene, to work hard, to treat the cast and crew fairly. She often mentors young women, in part because she could have used that mentorship when she was younger. Imogen Faith Reid, the actress who plays the adopted girl in “Good American Family,” appreciated that care.

“She would remind me that I could always speak up and have a voice,” Reid said. “It was just so amazing to hear.”

By the time Pompeo rolled up to LACMA, all that work was done. What would come next was out of her control.

“Maybe people will watch this and hate it,” she said. Or maybe they would love it, and then other scrubs-less roles would come. There were so many other women in that room of Picassos — seated women, weeping women. There were dozens of perspectives to explore.

However “Good American Family” is received, Pompeo will make peace with it. No, she doesn’t have the awards or the fashion campaigns or the prestige of an A-list movie star. But she has the respect of her peers and the love of her fans. And she has her family. It’s enough.

“I’m so happy with what I’ve done,” she said. “I’m happy with my fate.”