What to watch at the Fed meeting.

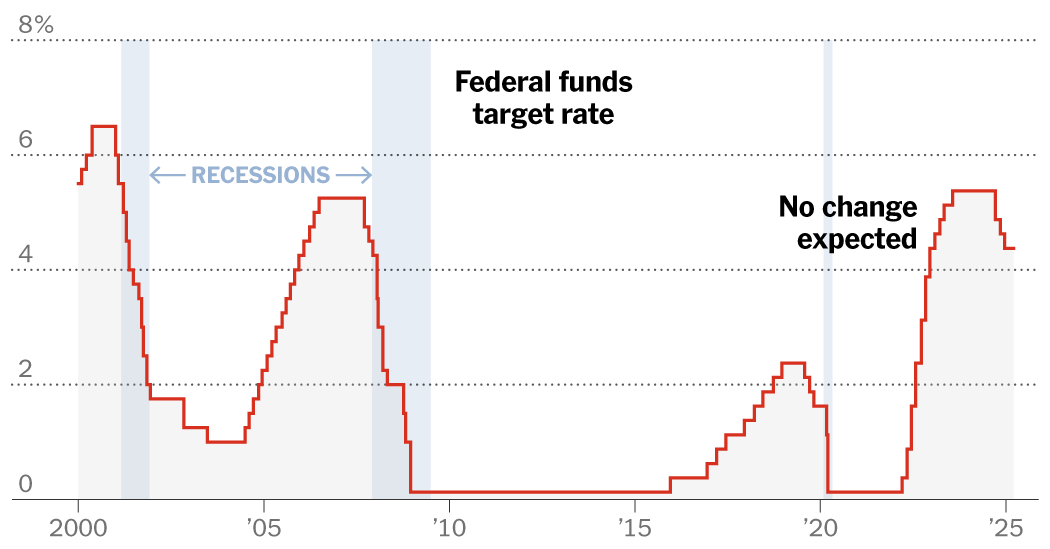

Federal Reserve officials are scheduled to release their first set of economic projections this year, alongside their interest rate decision, on Wednesday. Those forecasts will offer a fresh glimpse of the trajectory for monetary policy at a highly uncertain moment for the central bank.

Policymakers paused interest rate cuts in January after reducing borrowing costs by a percentage point in the latter half of last year. They are expected to again stand pat on Wednesday as they await greater clarity on how far President Trump will push his global trade war and to what extent he will follow through on other central aspects of his agenda, including slashing government spending and deporting migrants.

The big question now is when — and to some extent whether — the Fed will be able to restart cuts this year.

When the Fed last released quarterly economic projections in December, officials penciled in two rate cuts that would reduce borrowing costs by half a percentage point in 2025. But economists now expect Mr. Trump’s policies to lead to more intense price pressures and slower growth, a tough dynamic for the central bank and one that could prompt policymakers to scale back how many cuts they project going forward.

Here’s what could change and how to interpret those updates.

The dot plot, decoded

When the central bank releases its Summary of Economic Projections each quarter, Fed watchers focus on one part in particular: the dot plot.

The dot plot will show Fed policymakers’ estimates for interest rates through 2027 and over the longer run. The forecasts are represented by dots arranged along a vertical scale — one dot for each of the central bank’s 19 officials.

Economists closely watch how the dots are shifting, because that can give a hint about where policy is heading. They fixate most intently on the middle, or median, dot. That is regularly quoted as the clearest estimate of where the central bank sees interest rates going over a given time period.

The central bank is trying to achieve two things when it sets policy: low, stable inflation and a healthy labor market.

When it perceives elevated inflation to be a concern, it raises interest rates to make borrowing money more expensive, which cools the economy. By taking steam out of the housing and labor markets — as it did between March 2022 and July 2023 — higher rates helped to weaken demand and made it harder for companies to raise prices without losing customers, eventually weighing on inflation.

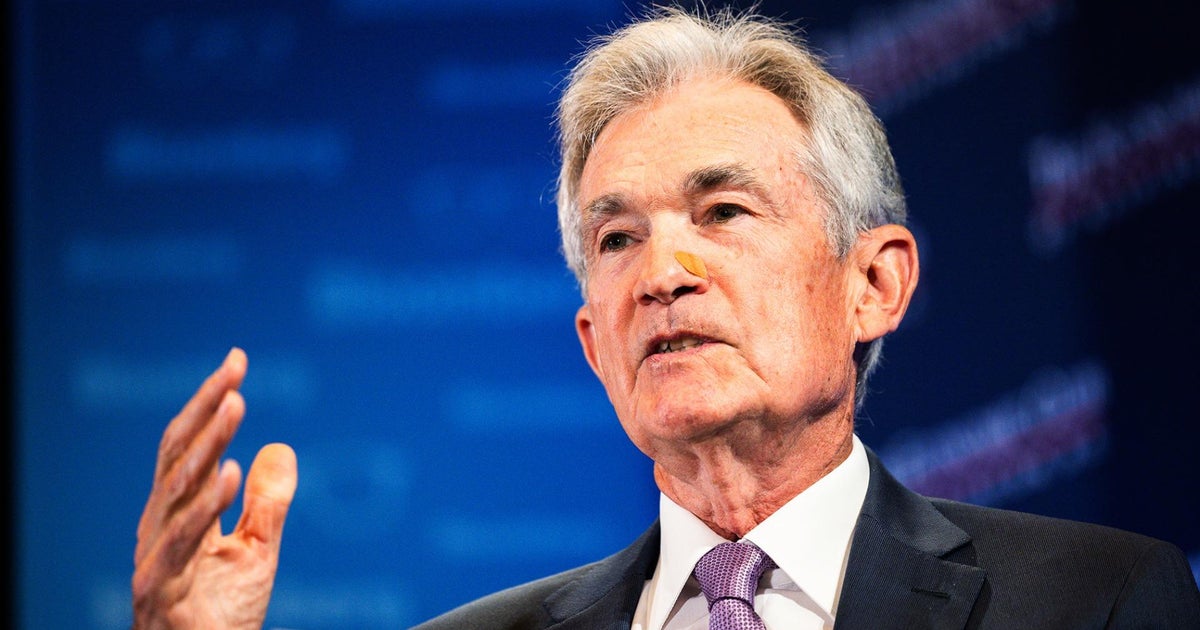

With inflation more in check, officials began cutting rates in September, kicking off with a big half-percentage-point reduction. At the time, the Fed’s chair, Jerome H. Powell, billed it as a move that would help to safeguard a strong economy, rather than a panicky response to unexpected weakness. The Fed lowered interest rates twice more in 2024, bringing them down to the current level of 4.25 percent to 4.5 percent.

Based on shifting perceptions about the risks around inflation and growth, economists broadly expect officials to pencil in either one or two quarter-point cuts for this year.

Are interest rates still restrictive?

When reading the dot plot, it’s important to pay attention to where interest rate estimates fall in relation to the longer-run median projection. That number is sometimes called the “natural” or “neutral” rate. It represents the theoretical dividing line between monetary policy that is set to speed up the economy versus a policy meant to slow it down.

The neutral estimate has steadily ticked higher in the past year and in December stood at 3 percent.

At the last meeting, Mr. Powell described rates at their current level as “meaningfully restrictive,” suggesting the Fed sees its policy settings as continuing to weigh on the economy and helping to bring down inflation. Economists will be watching whether the chair changes his tune on that point. If he suggests that rates are no longer as restrictive, it could mean the Fed now sees less capacity to lower rates with inflation still too high.

Inflation concerns resurface

Price pressures have eased significantly since peaking in 2022, but inflation overall has yet to return to the Fed’s 2 percent target. Progress toward that goal has been very bumpy in recent months, and with Mr. Trump seemingly committed to an aggressive tariff regime, there is increased concern about this progress could get thrown even further off course.

Fed officials moved their estimates for inflation sharply higher in December, with some already starting to layer in assumptions about what to expect from another Trump administration at that point. Back then, the majority expected the core personal consumption expenditures price index — which strips out volatile food and energy items and is the Fed’s preferred gauge — to hover at 2.8 percent by the end of the year. As of January, it stood at 2.6 percent.

Policymakers could raise those estimates again on Wednesday given the scope and scale of Mr. Trump’s plans to date.

Economists and policymakers broadly agree that tariffs lead to higher consumer prices, but whether those increases lead to persistently higher inflation is not entirely clear. Much will depend on how extensive the tariffs end up being, how long they are kept in place and ultimately how businesses and consumers respond.

Is the soft landing at risk?

As much as economists and policymakers are worried about resurgent inflation, they are also concerned about growth, despite the labor market having been much more resilient than expected despite soaring inflation and elevated interest rates.

In December, Fed officials expected the economy to grow 2.1 percent this year, a more moderate pace than 2024 but still a healthy clip. They also expected the unemployment rate to steady around 4.3 percent, 0.2 percentage point higher than its level as of February.

Estimates pertaining to growth are likely to be lowered in the latest set of projections, while unemployment forecasts could rise as officials factor in Mr. Trump’s plans to cull the federal work force and cut spending more broadly.

Americans’ feelings about the economy have already significantly soured on fears that all of the uncertainty surrounding Mr. Trump’s trade policy will also lead businesses to halt investment and hiring. Still, most economists do not expect a recession, given the economy’s strong foundation.