The Incredibly Beautiful Works of the Texan who Designed for Hermès

Across the delicate silk of an Hermès scarf, a handsome turkey struts. A closer look reveals a ring of illustrated cacti, flowers, and so many animals—an armadillo, birds, a steer. This is Faune et Flore du Texas, just one of the gorgeous scarves on display at Kermit Oliver & Hermès: Storytelling on Silk & Canvas, a new exhibition on a fascinating artist that runs through June 22 at the Bryan Museum in Galveston, Texas.

“I really just want Kermit to be celebrated,” says Meg Tucker, the museum’s programs manager, who curated the exhibition. “He’s so humble but he is a phenomenal artist. Each piece tells its own story that is both innate to Kermit’s style but also the history of Texas.”

Oliver, who was born in 1943 and grew up the son of a cowboy in Refugio, Texas, rose in popularity in Houston in the 1960s and 70s for his portraits on canvas. In a twist of fate, the cofounder of Neiman Marcus department stores saw Oliver’s work in a Houston gallery and recommended him as a possible contributor for Hermès, the renowned French fashion house.

Armillary, 2014.

The relationship that solidified between the Texan and Hermès is the stuff of artist dreams—Oliver became the first American to design the iconic scarves, and between 1984 and 2004 he created seventeen of them. “He would paint watercolors on a piece of paper that was the exact dimensions of the scarf,” says Tucker, who says she learned about Oliver’s process from a 2012 Texas Monthly article. “He would roll it up and send it to France. It almost sounds too simple to be true, when you look at how romantic and incredible these pieces are.”

Kachinas, 1992 35″x35″, Silk.

All of his pieces for Hermès tie to Texas in some way—through flora, fauna, cowboy, and Native American motifs, for example—and all of them are on display at the Bryan right now. In addition to the scarves, the exhibition displays some of what Kermit calls his “painted collages,” or assemblages of religious iconography, elements from nature, and sometimes, personal portraits. Poignantly, the curator included a portrait her grandmother commissioned from Oliver—of herself as a young girl, standing beside a horse and playful puppy.

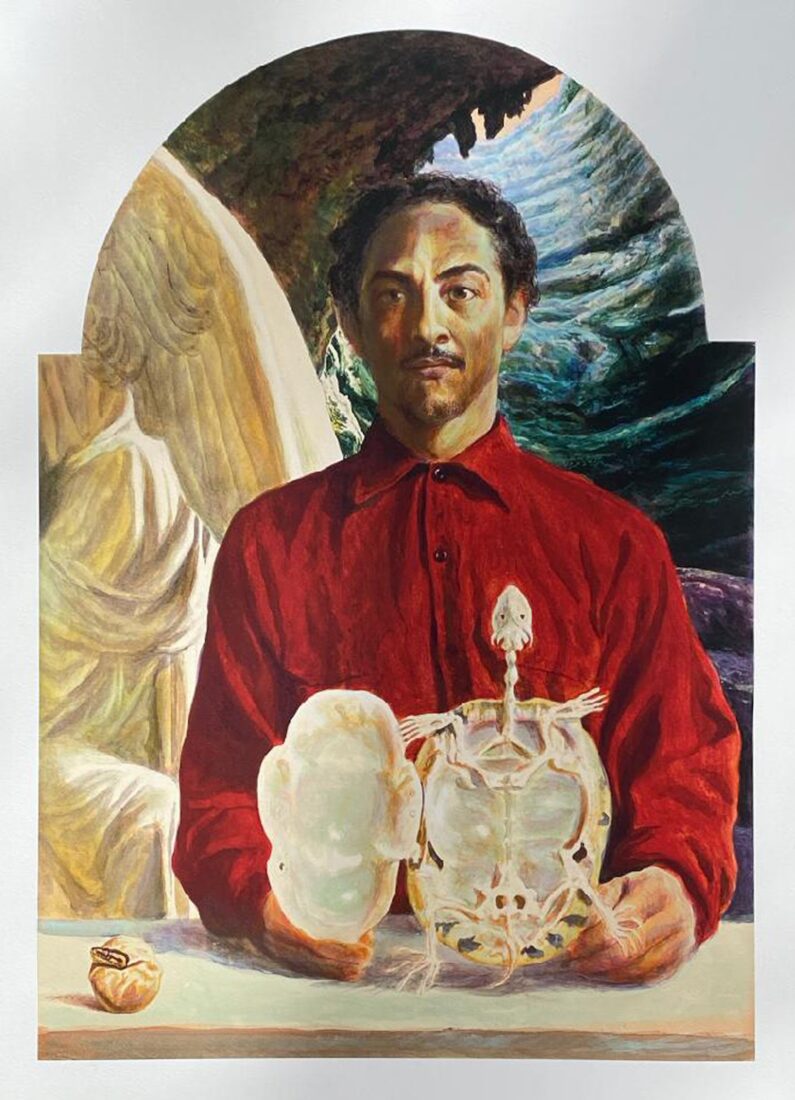

Orpheus and Eurydice, 1993, a self-portrait by the artist.

“Kermit lives in Waco, and my grandmother, Mickey Smith, was a real champion of his,” Tucker says. “Before I was even born, she had heard about how famous he was in Houston, so she told all her Waco friends, ‘This amazing artist is right under our noses here in Waco, let’s commission him for portraits.’ He painted my family and then later painted me, too.”

Texas, it turns out, has long loved the artist who has reflected its beauty on the world stage.

Find more information on the exhibition and its related events here.