Armand LaMontagne, Meticulous Sculptor of Sports Greats, Dies at 87

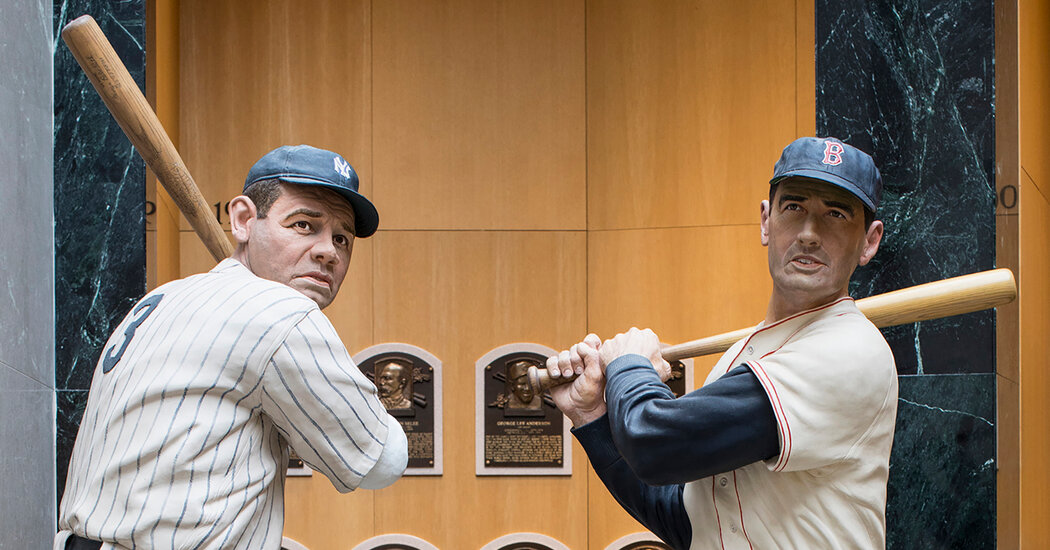

Armand LaMontagne, a Rhode Island sculptor who carved 2,000-pound blocks of laminated basswood into life-size renderings of larger-than-life sports figures like Babe Ruth and Ted Williams — two of which, like the players they depicted, ended up in the Baseball Hall of Fame — died on March 7 at his home in North Scituate, R.I. He was 87.

His daughter, Lisa LaMontagne, said the cause was heart failure.

Mr. LaMontagne began earning a place in the hearts of New England’s rabid fan base in the 1980s with his painstakingly detailed representations of beatified Boston Hall of Famers like Ted Williams and Carl Yastrzemski of the Red Sox, Bobby Orr of the Bruins and Larry Bird of the Celtics.

“In one of the great sports regions on the planet, Armand LaMontagne immortalized its sporting heroes in a way that was equal to that of the accomplishments of his subjects,” Richard Johnson, the curator of the Sports Museum, located in TD Garden, the home of the Celtics and Bruins, said in an interview.

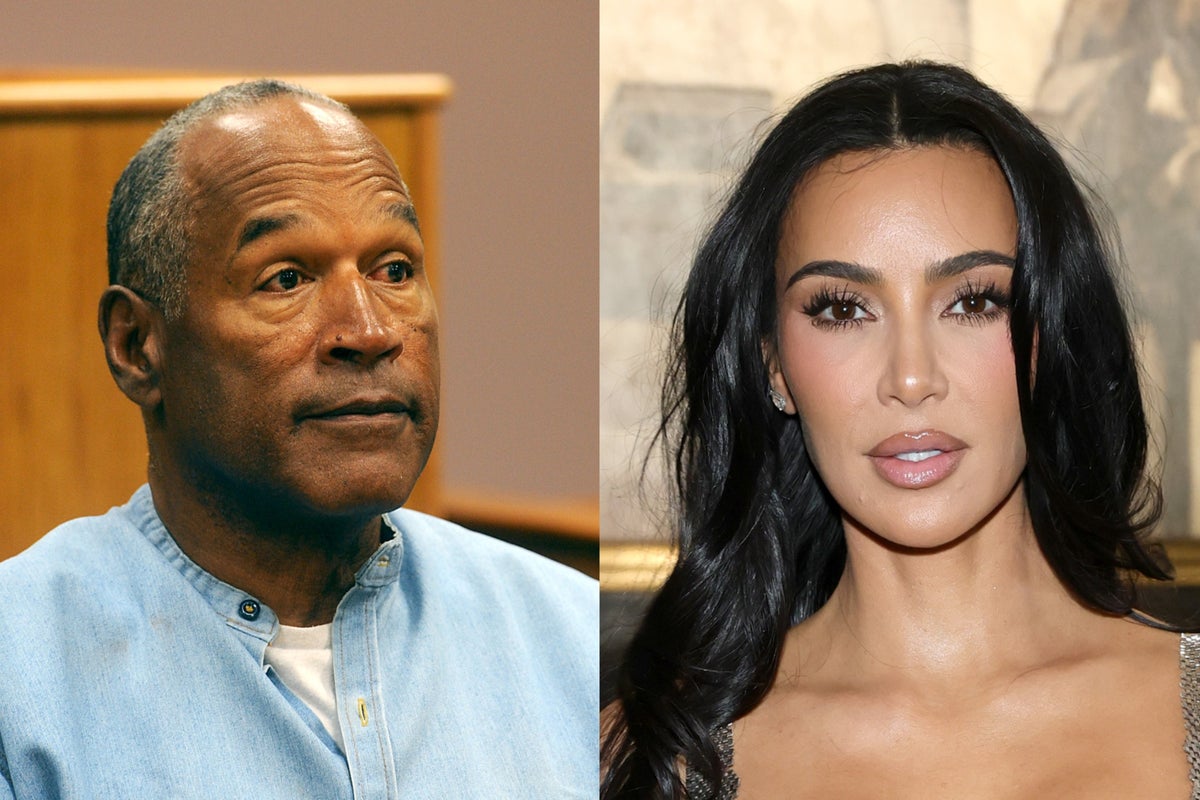

One of Mr. LaMontagne’s best-known works is one sure to cause anguish among those who consider Fenway Park their summer home. His sculpture of Babe Ruth, the Boston Red Sox star whom the team owner, Harry Frazee, famously — or infamously — sold off to the New York Yankees in 1920, was unveiled in all its pinstriped glory in August 1984 at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

As noted in a 2020 profile of Mr. LaMontagne in The Athletic, the sports site now owned by The New York Times, Red Sox fans could breathe a sigh of relief when his rendering of Williams, commissioned by the Sox owner Jean Yawkey, joined the Bambino in the Hall the next summer. (Mr. LaMontagne created another sculpture of Williams in fishing gear to commemorate the man known as the Splendid Splinter’s other favorite sport.)

Mr. LaMontagne began making his signature sports sculptures studio attached to his house in North Scituate — a replica of a so-called Rhode Island stone ender design from 1680 — which he built himself in 1973.

To achieve lifelike results for his wooden sculptures, which were sometimes later cast in bronze, he invited his famous subjects — those who were still alive, at least — in for a fitting of sorts, measuring their arm lengths, thigh circumference and so forth, and then photographed them in an appropriate sporting pose. For Ruth, Mr. LaMontagne worked from photographs, as well a from loaner uniform of his.

Tracing the pose from the photograph on a massive block of kiln-dried wood, Mr. LaMontagne then labored for up to 10 months, topping off the work with an acrylic paint job executed to the same exacting degree of detail. (He was also a painter; his portraits of athletes and other notables are on display throughout New England and beyond.)

He sometimes had to make his own tools for specialized tasks. As Mr. Johnson put it, “You can’t go to a woodworking store and buy a tool to carve the dimples on a basketball.” (The wooden basketball that his Bird sculpture crouches to shoot had some 4,000 such bumps, or pebbles, his daughter said.)

The Celtics unveiled the lumber alter ego of Bird, a foundational star of their three championship teams of the 1980s, during halftime of a home game in February 1988.

“The only thing about Armand, he was all right from the head down to the waist,” Bird recounted at a news conference at the time, “but when he started beating around with that chisel and hammer down there a little bit lower, I could feel it at night.”

Armand Maurice LaMontagne was born on Feb. 3, 1938, in Pawtucket, R.I., the second of eight children of Raymond LaMontagne, a construction superintendent, and Jeanne (Ferland) LaMontagne.

He was an all-state fullback for Pawtucket Vocational School before transferring to Worcester Academy in Massachusetts, where he earned a football scholarship to Boston College.

Struggling with his studies because of dyslexia, he left college after two years. Following a stint in the Army, he briefly worked as a state trooper before turning to another early love, art, eventually earning a grant to study marble sculpture in Florence, Italy.

For years he earned money by making handcrafted period furniture and decorative wood sculptures. His first official sculpture portrait, as he called them, was a likeness of Gen. George S. Patton, the fabled World War II commander, which was unveiled in 1983 at the General George Patton Museum of Leadership at Fort Knox, near Louisville, Ky.

In addition to his daughter, Mr. LaMontagne is survived by his wife of 61 years, Lorraine (Robitaille) LaMontagne; his sisters, Lucille Coutu and Anne Gaboriault; and his brother, Henry LaMontagne.

As an amiable ex-jock, Mr. LaMontagne established an easy rapport with his luminary subjects. He told The Athletic that Bobby Orr was “a nice guy when he wasn’t playing hockey,” and that Larry Bird “worried about everything” but was “a great guy.”

Then again, he added, “They’re all nice to the guy who can make them look ugly forever.”