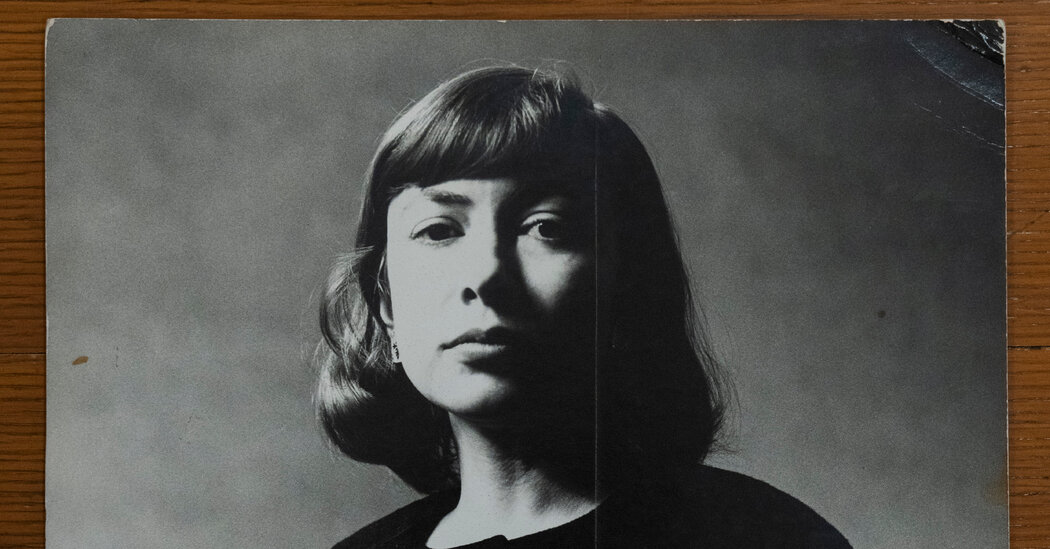

For Joan Didion, Mementos of Her Daughter’s Childhood Became Material

An arrangement of dried flowers pressed between sheets of plastic, the name “Quintana” written in a child’s neat lettering at the top.

A yellow Post-it with a poem written in cursive: “My mom is not a sigh/She does not eat pie/Maybe she can fly.”

A pocket-size notebook of handmade paper composed as a Mother’s Day gift in which the now adult daughter, Quintana, had pasted a series of photographs she’d taken of her mother, Joan Didion, on a television screen, her own blurry toe visible in the foreground, followed by a note in green ink: “Thought you might want to see yourself again. … To, of course, the best mom ever!”

The mementos are the sort any parent would collect: amateur artwork, loosely scribbled missives and a piece of scrap paper bearing the daughter’s “autograph,” above her self-identification as an “Up and Coming Singer, Actress & Comedian.”

But Didion, who died in 2021, did not store these particular keepsakes among the family’s personal belongings; rather, she filed them as research materials for her work — together with the notes, articles and early drafts she drew on while writing “Blue Nights,” her 2011 memoir of the death of her only daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, at 39.

This poignant and revelatory ephemera from Quintana’s life is among the 240 linear feet of joint archives of her writer parents, Didion and John Gregory Dunne, now available for viewing at the New York Public Library. Together the research files offer physical evidence of how embedded Didion’s personal life was in her professional work — even, or perhaps especially, her most painful experiences.

Alongside these mementos Didion kept a stack of undated, printed pages she titled simply “NOTES.” Around 20 pages in all, the pages are numbered, but some numbers repeat, suggesting she’d originally written them as separate documents, and perhaps later stashed them together. The notes within pertain not only to “Blue Nights,” but also to 2005’s “The Year of Magical Thinking,” her National Book Award-winning account of another death that overlapped in time with Quintana’s — her husband John’s.

What happened, chronologically, was this: On Christmas 2003, Quintana was hospitalized for a flu that turned into pneumonia that turned into a coma. Five days later, upon returning home from visiting his unconscious daughter in the I.C.U. on Dec. 30, Dunne died suddenly, at the dinner table, of a heart attack that had been foretold for years but was nonetheless over in the span of an “ordinary instant,” as Didion wrote in the 2005 book.

A year and a half later, on Aug. 26, 2005, after a torturously protracted series of health emergencies whose precise causes Didion leaves somewhat opaque (the Christmas flu that turned into pneumonia then turned into septic shock, and eventually into a cerebral hemorrhage), Quintana died too.

“I write about this because otherwise I would be dead,” Didion typed in the “NOTES” document. “This is not a book I want to finish. When I finish we will be finally apart.”

Based on the entries immediately before and after these lines, she seemed to be referring to “Magical Thinking,” but there is no clear demarcation in the file between the thoughts Didion intended for one grief memoir versus the other. Given that the timelines of these two catastrophic losses were so entwined, it’s not surprising that her notes about them would be too.

Except that Didion completed “The Year of Magical Thinking” in just a few months, barely a year after Dunne’s death — “I began this account on Oct. 4, 2004,” she write in the same notes file, “I am finishing it on the last day of 2004” — whereas “Blue Nights” has none of the same sense of immediacy. Quintana died six weeks before “Magical Thinking” was published; Didion would not publish “Blue Nights” for six more years.

Although written in a truncated, deeply referential manner that suggests their only reader was to be herself, Didion’s notes reveal the steps in her writing process. They also reveal details of her family’s life that her books do not. (A journal of conversations she had with a therapist starting in 1999, “Notes to John,” will be published next month.)

Beside a memory of having been so panicked at Quintana’s first loose tooth that “my sole remaining thought was to get her to the emergency room at U.C.L.A. Medical Center, 30-some miles into town,” whereupon Quintana’s cousin Tony swiftly pulled the tooth with his bare hands, Didion adds by hand in the margins: “Was I the problem? Had I always been the problem?” These lines made their way into “Blue Nights,” almost verbatim.

What did not make it in: “I did not understand addiction.”

The materials reveal firsthand the simultaneous levity and depth of Quintana’s relationship with her parents, the “quicksilver changes” Didion would observe in her daughter’s personality throughout her life.

Among the material in the collection is a collage of photo cutouts Quintana made while she was working as a photography editor at Elle Décor in her 20s. Her casual humor with her parents is evident in the handwritten letter on pink paper on its opposite side: “I want you to look what J.F.K. is pensively staring at.” To the right of the cutout of the former president in profile is a cropped photo of a woman’s butt and thighs in a tight miniskirt. “Sorry — this is just a stupid, highly obvious little joke I thought was amusing.”

A few days later, she continued writing the note with a more heartfelt expression of gratitude for her parents’ tough advice. “I cannot tell you how good this N.R.T. has been for me,” she said, seemingly referring to nicotine replacement therapy. “It’s amazing how clear and evident my ‘winding down’ from Bennington has been. What I mean to say is that all the things you were saying to me in Los Angeles seemed so meaningless and foreign to me. … Well, as usual, you were both right.”

There is only one passing mention in “Blue Nights” of Quintana’s substance use: “Because she was depressed and because she was anxious she drank too much. This was called medicating herself.” Didion doesn’t say in the book whether her daughter’s drinking contributed to her cascading illness. She spends more time dissecting, belatedly, Quintana’s complicated feelings about her own adoption.

“I had seen the charm, I had seen the composure, I had seen the suicidal despair,” Didion wrote in the book. “What I had not seen, or what I had in fact seen but had failed to recognize, were the ‘frantic efforts to avoid abandonment.’”

“Adoption was an area that John and I could not discuss until very late,” she wrote in her notes. “Q worrying about how I would cope, how she would cope with me.” These sentences alone are underlined in pen, but they never made it into the book.

Much of Didion’s published writing, particularly about her daughter’s mental health (she was given many psychiatric diagnoses over the years, culminating in multiple personality disorder), can feel like a whisper the reader strains to hear, but never quite does. What we do hear, loud and clear: the day Didion and Dunne brought her home from St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, Calif.; her coming-of-age among the cultural elite in Hollywood, Malibu and Brentwood; her lei-garlanded Upper West Side marriage to the musician and bartender Gerry Michael, only months before she got sick.

“LOOK AT: the history of the nuclear family,” Didion jotted. Also:

The Christmas cards.

The “princess” dresses.

The time I took her on tour

“In fact I no longer value this kind of memento,” she wrote in “Blue Nights” of the baby tooth she saved in a satin box after Tony pulled it.

“I believed that I could keep people fully present, keep them with me, by preserving their mementos, their ‘things,’ their totems,” she wrote. “In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.”

She kept them anyway.