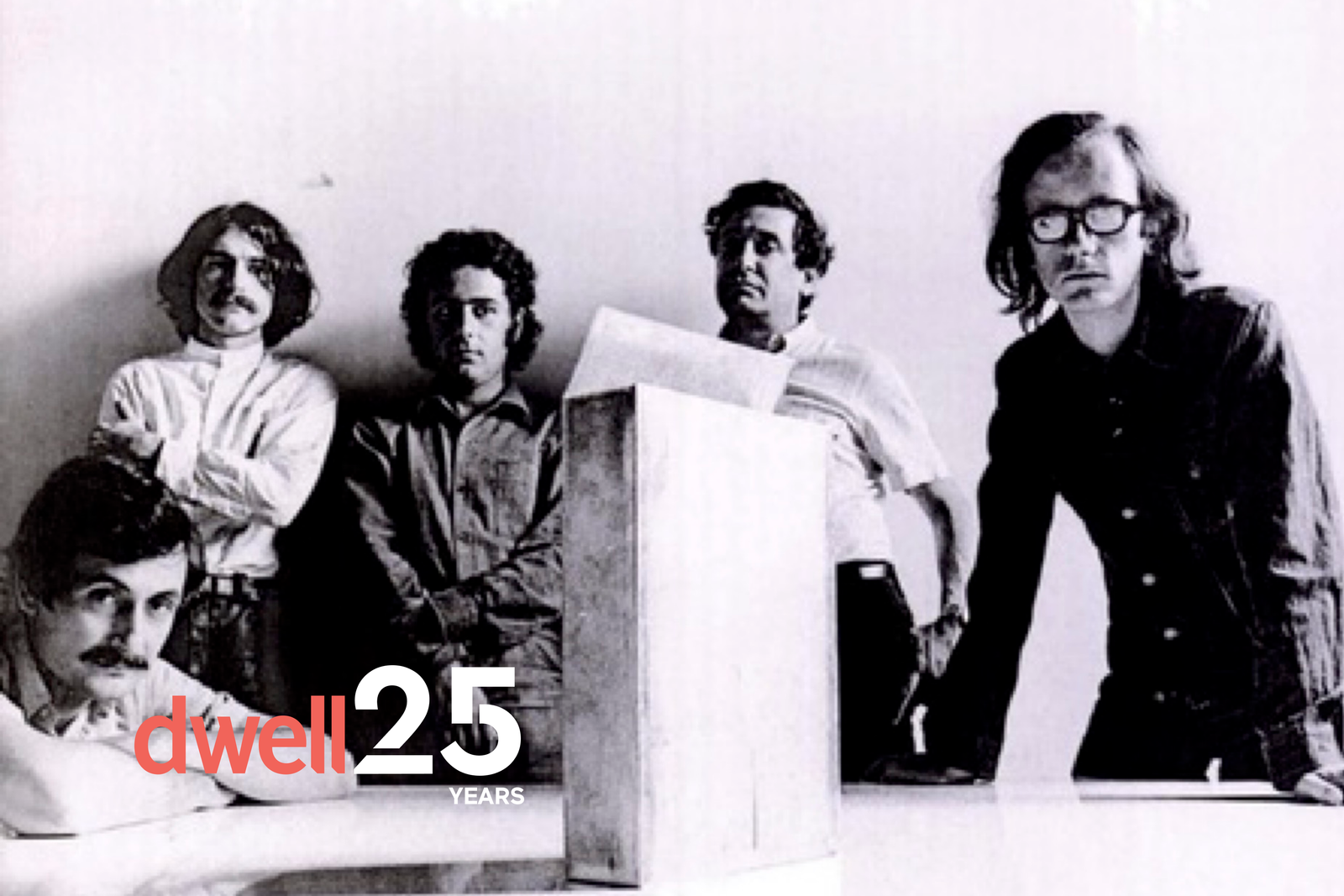

From the Archive: How Renegade Architecture Firms Challenged the Status Quo

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s July/August 2006 issue.

“In science fiction we dig out prophetic information regarding geodesic nets, pneumatic tubes and plastic domes and bubbles….Our document is the space comic; its reality is in the gesture, design and natural styling of hardware new to our decade-the capsule, the rocket, the bathyscope, the Zidpark, the handy-pak.”

These words, excerpted from editorials in Archigram 3 and 4 (1963 and 1964) and penned by Peter Cook, cofounder of the new defunct London-based architecture collective Archigram, express the excitement of a period beginning is the early ’60s when renegade architects around the globe questioned the very fundamentals of architecture, from its relationship to society to the production of buildings.

Influenced by the roiling movements in art, media, politics, and technology, they had names and group identities that bring to mind rock bands rather than architecture firms: the Metabolics, Superstudio, Ant Farm, and Archizoom. Instead of designing buildings, they more often created fantasy utopias, entire cityscapes on paper that were never built but which excited an entire generation and encouraged a wholesale reevaluation of the built environment.

In different ways and through different media—from gonzo graphics to film to performance art—many of them explored the impact of new materials, production processes, and the mobile lifestyle promised by the auto and aeronautical industries and information technology. “All of them were dealing with different modes of communicating architecture,” says David Erdman, cofounder of the design collaborative Servo. “And they were developing new languages of architecture that dealt with the new things it contained.”

Analyzing and critiquing the pervasive corporate modernism and overly rationalist urban planning of that period, these architectural outcasts seized on irony and wit to make their point. “This was a breakthrough moment when the explosion of new materials and radical lifestyles were driving a vision of architecture that was vaguely nomadic and not oriented toward the acquisition of possessions,” explains Craig Hodgetts, architect, professor of architecture, and longtime friend of the Ant Farm group. “The ideal was not the luxury bath we see today but the airplane bathroom.”

These collectives “introduced whimsy and subjectivity and insolence and irony back into architecture,” says Stephen Nowlin, director of the Williamson Gallery at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. “At the time it was almost sacrilegious that they would do this. But that constructive insolence is one of the most important things you can teach in a design school.” In recent years there’s been a renewed interest in these counter movements with numerous traveling exhibits and academics doing weighty scholarship on their work.

The most influential and productive collective was Archigram, the eldest of the renegade groups. Its members (Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Mike Webb) created an astonishing 900 drawings of pen-and-ink and collaged images between 1961 and 1974. The six met in the late ’5os while holding down day jobs at a large construction firm in London. Their nights, however, were spent feverishly drawing imaginary, mobile, temporary environments with electronic age names like the Capsule Home, the Plug-in City, and the Walking City, a megastructure that could plod across the land like a vast robotic animal.

They published their projects, along with essays and poems and the work of other designers they considered to be coconspirators against the establishment, in nine issues of an underground magazine they collaged together called Archigram, first published in May 1961.

Today, Cook explains the group’s goal succinctly: “We wanted to put the zap back into architecture.” Archigram, he says, was driven by a passion for technology and art, while some of the other groups were motivated by politics. “Three out of six of us had been to art school before architecture school,” Cook says. “We were all mixed up with art students. Our ladies were art students. I can’t speak for the Italians, they always have political layering that doesn’t interest me.”

For groups like Ant Farm and Superstudio, however, which formed when students worldwide were in revolt, politics was central. Architecture grads Chip Lord, Doug Michels, and Curtis Schreier founded Ant Farm at a time and place ripe for rebellion—San Francisco in 1968. “The year l graduated was the time of the antiwar movement, so we embraced wholeheartedly a form of radicalism,” Lord explains. “At the beginning we were a kind of commune, and people came and went, like a lot of bands, the Grateful Dead or Jefferson Airplane.”

Meanwhile in Florence, Italy, Superstudio, an Italian gang of five—Adolfo Natallini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Alessandro and Roberto Magris, and Gian Piero Frassinelli— rejected the optimistic view of technology’s ability to improve the world. Instead, they attacked architecture and politics with ironic commentaries in the form of photo montages, sketches, and storyboards for having aggravated the world’s social and environmental problems. They created what they called “negative utopias,” home to an “antidesign” culture in which everyone would be given a sparse but functional space to live in, free from superfluous objects.

Despite the frenetic force and boundless enthusiasm with which these groups delivered their messages of architectural rebellion, the radical architects of the ’60s and ’70s slowly petered out with the advent of the oil crisis, Reaganism, and a subsequent decade of kitschy postmodern architecture.

Some admirers of these countercultural architects wonder where the radicalism is today. Maybe it has diminished because the visions of these groups came to pass or because it’s no longer clear who the adversary is. “Popular political themes today are less discernible and much broader and more nuanced,” says Servo’s Erdman. Adds Ant Farm’s Lord, “The new generation has many more options of how to define an architectural practice,” referring to the multidisciplinary nonhierarchical firms that exist today. He adds that design possibilities for building have exploded: “Today there is more access to different styles, and more technological freedom.”

On the other hand, some say that architects who question the fundamentals of design and society haven’t vanished at all, they’ve merely morphed. The radicalism may not be in unbuilt, paper utopias but in actual buildings, by a new generation of quiet revolutionaries. “Today’s counterculture architects,” says Nowlin, of Art Center’s Williamson Gallery, “are those who are really exploring green architecture and radical new ways of how we shelter ourselves in new situations. They are challenging relationships with the whole machinery of how architecture gets made.” You won’t see spectacular drawings of fantasy techno-whizzy cities, like Archigram’s, or poetic images critiquing civilization like those of Superstudio, or subversive performance pieces like Ant Farm’s. “It’s a different sensibility, not whimsical or ironic,” Nowlin says, “but nonetheless it does at the same scale challenge what has come before.”