George Foreman beat time by going from humiliation to vindication

As he entered the public consciousness — a big man waving a tiny American flag as if it were a conductor’s baton — George Foreman was definitely not of the moment. This was 1968, at the Mexico City Olympics. The cool kids, not to mention the righteous ones — American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos – took to their medal stand with gloved fists raised, their way of acknowledging America’s perennial difficulty with racial justice.

If Smith and Carlos were princes of protest — I mean, really, whatever your politics, it’s difficult not to admire what they did that day — then Foreman was an altogether different kind of archetype. In the continuum of boxing, the delinquent out of Houston’s Fifth Ward was “The Scary Guy,” the successor to Sonny Liston. Goliaths are not there to be loved, just feared.

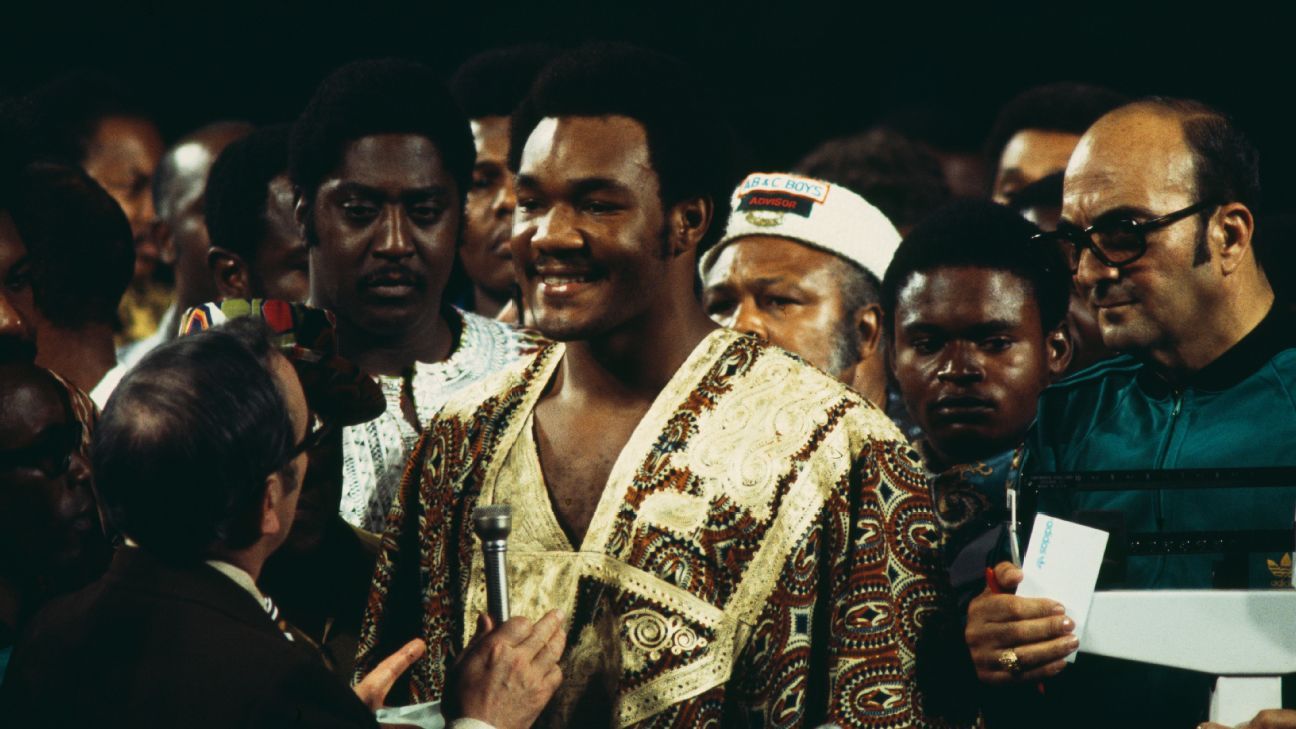

And Foreman made it easy, his reputation as a soul-crushing behemoth crystallized on Jan. 22, 1973, at National Stadium in Kingston, Jamaica, when he fought Joe Frazier. Frazier, as tough a heavyweight as ever there was, wasn’t merely undefeated (when being an undefeated heavyweight actually meant something), he was still basking in the glow of his epic 15-round defeat of Muhammad Ali. Still, Foreman put him down six times that night – resulting in Howard Cosell’s impossible-to-ever unhear call “Down goes Frazhuh!” — before referee Arthur Mercante Sr. called a merciful end to the bout. It’s worth noting, too, that with each knockdown, promoter Don King — who had ridden to the stadium in Frazier’s limousine — moved physically closer to the Foreman camp. Needless to say he returned to his hotel in Foreman’s limo. “I came with the champion,” King liked to say, “and I left with the champion.”

More important, it was King’s theatrically heartless sense of commerce that made for his signature promotion, almost two years hence, in Zaire. “The Rumble In the Jungle,” as it was christened, featured an apparently diminished Ali (by now, his jaw had been broken by Ken Norton) against an apparently indestructible Foreman (who had dispatched that same Norton even more quickly than he had Frazier). What’s more, Foreman retained the same sense of tone-deafness that he had back in the ’68 Olympics: walking around with his prized German shepherd, Dago, unaware that such dogs had been used as tools of oppression by Belgian security forces when Zaire was a colony known as the Congo.

What Ali did in Zaire isn’t merely the foremost example of his improvisational and strategic brilliance, but his bravery. Ali’s rope-a-dope, as it came to be known, required that he absorb the Bully’s best shots for, in this case, the better part of seven rounds, before Foreman tired and Ali took him down. Foreman fell face-first from a series of vicious right hands.

This wasn’t the end anyone — outside, perhaps, of Ali — had envisioned. The sage ex-champ Archie Moore, who was working Foreman’s corner that night, would recall in Norman Mailer’s “The Fight”: “I was praying, and in great sincerity, that George wouldn’t kill Ali. I really felt that was a possibility.” As it turned out, though, the only fatality that night was Foreman’s sense of invincibility. But a bully who’s no longer feared is a bully undone. Zaire seemed to leave Foreman psychiatrically disfigured.

He didn’t fight for another 15 months. Then, in 1977, following a unanimous decision loss to a crafty if light-hitting Jimmy Young, he felt something, as if he were dying. It had been a grueling fight on a sweltering night in Puerto Rico. Perhaps it was heat stroke? No, said Foreman, it was the voice of God. It was telling him to retire and become a preacher back in Houston, which he did.

A decade later, his church in need of money, Foreman embarked on another comeback. Boxing is full of guys who fought tragically past their primes, but this was something entirely different. From Don King to Jay Gatsby, it’s a uniquely American trait, the ability to reinvent oneself. Still, Foreman’s reinvention remains without precedent. The surly, bully returned fat, happy and religious to boot. So fat and happy, in fact, he would go on to set records as the seller of his eponymous hamburger grill. Still, his talent for commerce obscured his historic athletic accomplishment.

I was there the night of Nov. 5, 1994, at the MGM Grand, when Foreman — whose “comeback” had long been considered something of a novelty — fought the heavyweight champion, Michael Moorer.

Moorer was a talented champion in his physical prime, and a southpaw to boot. He had an excellent corkscrew jab, and was very well trained by Teddy Atlas, who kept reminding his fighter (and everyone else who would listen) that Mr. Fat and Happy was “a con artist.”

It occurs to me now that any champion worth a damn is part con artist. But Foreman’s true aptitude for subterfuge wasn’t truly evident until that night. He was two months shy of his 46th birthday and hadn’t fought in 17 months, not since a unanimous decision loss to Tommy Morrison. By way of comparison, the oldest man to win the heavyweight title, Jersey Joe Walcott, was 37 when he knocked out Ezzard Charles in 1951.

No surprise, then, that Moorer won eight of the first nine rounds, working behind that tough corkscrew jab. By now, Foreman’s face was lumpy and marked. Still, he knew exactly what he was doing. If this were con artistry, it was downright Ali-esque, his own answer, two decades hence, to the rope-a-dope. Above all, it was a stratagem requiring bravery and a singular belief in oneself. So Foreman ate those jabs and those hooks. If they exacted a terrible price, it was one Foreman was willing to pay for his chance — his only chance, in fact. It began with a slapping left hook that seemed to stun Moorer, then, an impossibly short right hand that landed flush on the young champion’s chin. Moorer was counted out at 2:03 of the 10th round.

The famous blow, that right hand, traveled mere inches. But those same inches traversed time and space, across decades and continents, from Zaire to Las Vegas, humiliation to vindication. The young guy beats the old guy. That’s the story of boxing — one of them anyway. But Foreman wasn’t merely an old guy, or even the oldest (in any division, mind you). Athletes are artists whose artistry dies with their youth. For fighters, it tends to be worse, as the youth is literally beaten out of them. But George Foreman — erstwhile bully, seller of grill gadgets and mufflers — did the greatest thing any athlete can do. He beat time.