How Salvador Dalí’s art found a home in Florida

When Mike Wallace interviewed Salvador Dalí in 1958, the painter seemed to believe that he might live forever. Asked what he believed would happen to him when he died, the Surrealist replied, “Myself not believe in my death.”

“You will not die?”

“No, no. Believe in general in death, but in the death of Dalí? Absolutely no, not.”

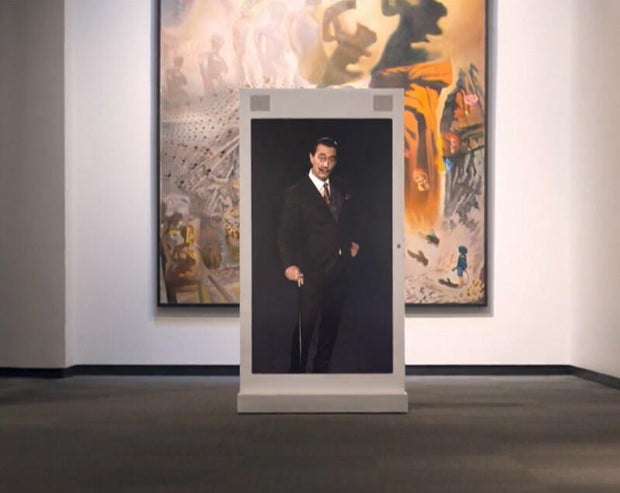

Dalí did die, in 1989. But in a way, he was right. The artist lives on at the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

CBS News

The collection chronicles his career through more than 2,400 of his works, from oil paintings to sculptural mashups to fine jewelry. Inside the Dalí Dome, a “Dalí Alive 360” show fully immerses visitors in his art.

“Its spirit is based in Dalí’s,” said Hank Hine, the executive director of the museum. “That is, Dalí was always trying to do things in new ways. The amazing thing about Dalí is that his impact is still felt today, not only in art, but in culture generally.”

CBS News

Today, Salvador Dalí may be a household name, but his name first belonged to his parents’ firstborn son. “His parents named him after his dead brother,” said Hine. “That saddled him with a burden of identity that lasted all his life, and can explain a lot of his art – for instance, his double images, where you see one thing, and you see another. So, this Salvador Dalí was always wondering, ‘Am I myself or am I the other?'”

Many of Dalí’s works combine the real and the surreal – a juxtaposition he could pull off thanks to his training as a precise classical painter. “He can paint like an old master; however, he wasn’t content to stay there,” said program director Kim Macuare.

She said Dalí found inspiration by diving deep into the subconscious: “He was very interested in the writings of the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. And so, when he cuts the drawers into the Venus, what’s he’s imagining is, ‘What would happen if we could go up and open the drawers and look inside someone to see what really makes them tick?'”

CBS News

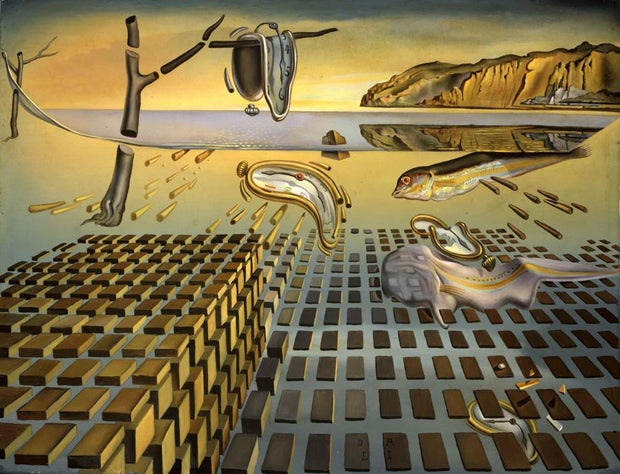

As far as ticking goes, Dalí’s famous painting of melting watches, “The Persistence of Memory,” is actually at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But his follow-up is here, hanging in a museum in a state Dalí never even visited.

The Dalí Museum

The artist had no connection with St. Petersburg, Florida. But what he did have were two very big fans. A wealthy Ohio couple, Eleanor and Reynolds Morse, bought a Dalí painting to celebrate their first anniversary, a purchase that kicked off a lifetime of collecting and friendship. They acquired everything from Dalí’s early Cubist paintings to his later, larger religious-themed canvases.

Hine said, “They loved Dalí so much that they bought only Dalí for four decades, and were able to put together what is the preeminent collection of Dalí in the world.”

CBS News

When the Morse family decided to donate their collection in the late 1970s, they were insistent that it all go to one location, but no museum stepped up. After the Wall Street Journal wrote an article (“U.S. Art World Dillydallies Over Dalís”), the people of St. Petersburg, Florida, said, “Well, heck, we’ll take it.” The city made an agreement to find a building for the collection – a marine warehouse that, in 1982, opened as the Dalí Museum.

In 2011, the collection moved to its current location, where the Morses’ son Brad now comes to see the paintings that once covered his childhood home. “There was not a square foot or inch even of wall space that wasn’t holding a Dalí painting,” he said.

In fact, Dalí’s 1956 oil painting “Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life-Fast Moving)” hung above Brad Morse’s bed.

CBS News

Now, more than 300,000 visitors a year come to see the fascinating ways in which Dalí saw the world.

Macuare said, “Dalí had a really great quote, and I think it’s indicative of how he saw himself and how he saw the world, and that was, ‘I don’t do drugs. I am drugs.’ He thought that seeing as he did would absolutely change your perspective.”

Dalí was perceived as an eccentric. Especially in his later life, he was known just as much for his wild persona as he was for his art. But in death his work has gained greater critical appreciation.

“I think the height of his fame is not over,” said Hine. “Dalí’s star is still rising in the world, largely because of what he suggested in his art about the ability to see the world in a different way, something that we really need in this world today.”

WEB EXTRA: Why are Salvador Dali’s clocks melting? (Video)

For more info:

Story produced by Jay Kernis. Editor: Chad Cardin.