I saved my dad from going into a care home – and I’m so relieved I did

I was stuck in a traffic jam with my dad when he reached over and held my hand. I’d just promised him that I would never let him go into a care home, that I’d stick by him no matter what. I meant it.

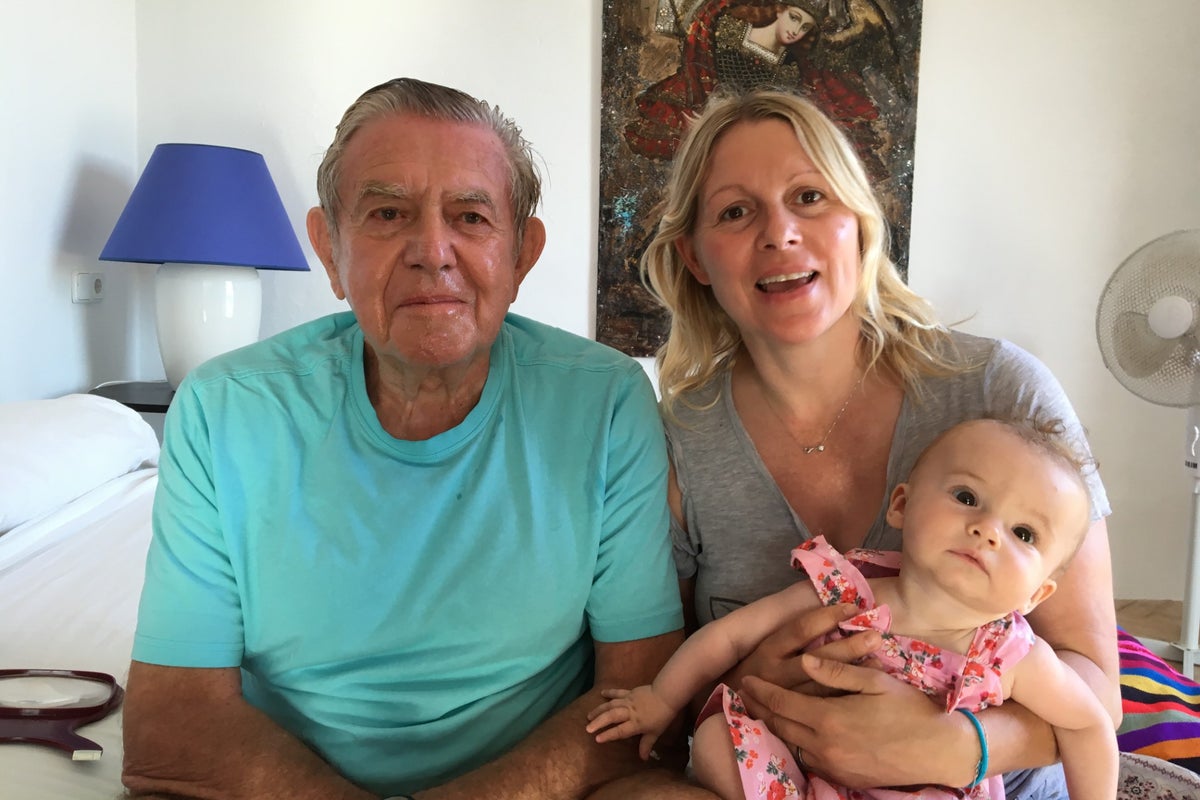

That was 15 years ago. I had no idea then that, when the time came, I’d be a single working mum with two children, Lola and Liberty, now eight and six, and juggling life as what is known as a “sandwich carer”. To be honest, I hadn’t pondered that decision in the car for more than a few seconds, but it was a profound and instinctive one. My dad died last summer at the age of 92. I was caring for him until the bitter end.

During my dad’s final years, I was one of the estimated 1.4 million individuals in the UK who care for elderly or sick relatives as well as dependent children, according to the Office for National Statistics. Not surprisingly, most of these sandwich carers (61 per cent) are female. It remains the daughters (or wives of sons) who often take on such a role, despite greater gender equality. For me, though, it was plain and simple: I didn’t want to send my dad off to a care home. The thought filled me with dread.

New research this week has revealed that almost one in five care homes in England are failing – including 40 per cent of homes in Liverpool, Halton and Camden.

According to the Care Quality Commission (CQC) regulator, 132 facilities in England were deemed “inadequate”, while another 2,418 were judged to “require improvement”. Four boroughs within London – Islington, Wandsworth, Westminster and my local borough, Kensington and Chelsea – had “sub-zero” care homes.

Professor Martin Green, the chief executive of charity Care England, this week criticised the “postcode lottery” faced by patients of all ages in terms of care home standards.

The funding crisis doesn’t seem about to improve, either; care homes are set to increase fees charged to local authorities by 8 per cent — over £3,000 more a year – to cover the higher costs from the Budget, according to Care England.

With shocking figures like this, I’m glad I saved my dad from a care home – although it was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. It’s not something everybody can do for an elderly parent, or wants to, but it was easier for me when my dad moved in with me than when I looked out for him from 20 minutes away. I had always seen care homes as a last-chance saloon, places you’d pay not to go to if you could help. I pictured nervous relatives installing secret cameras that revealed care neglect, and underpaid carers spoon-feeding dribbling mouths.

Of course, it’s sometimes the only option when relatives can’t manage for financial and practical reasons. I’ve seen plenty of nicer private care homes costing £100,000 a year minimum – or far more. My great aunt had been moved to a grand one near Suffolk; it didn’t resemble a care home, though. It was more like an ancestral stately home with a sprawling staircase and a Harrod’s Christmas tree, which I saw as a child when my mother took me to visit her for the annual Christmas lunch. Her high-ceilinged private rooms in the main house were decked out with all her artworks and gold antique French-style chairs, and she had round-the-clock nursing care.

I’d also seen the other, less glamorous side of care homes when my dad put his mother in one opposite his office near Barnes. It was a depressing semi-detached house off the main road. Although my grandmother had a front-facing double bedroom, I knew it was the end for her when I visited her. She’d lost her spirit. She only lasted a week. I was determined to make sure that, whatever happened, I would not leave my dad to that fate.

The first taste of what was to come happened just after I’d given birth to my eldest child, Lola, in 2016. I was on maternity leave, and my dad got seriously ill. He became delirious for weeks in Kingston Hospital. Doctors told me how important it was to have my familiar face there to give him a better chance of surviving the intense confusion. I sat at his bedside with my baby daughter for weeks until they moved my dad to intensive care at Tooting. No antibiotics worked – little did we know he had a rare infection in a disc in his lower back. I phoned around, desperate to get him the right help. Eventually, he was taken in an ambulance to a private hospital where an infectious diseases doctor worked it out. He was better within two days.

But it was the start of a slippery slope. No longer was my life my own, and not even having a second baby could get in the way of my dad. As time went on, after each hospital stay or every knock and fall, a little bit more of his independence went away. He refused a stairlift until the bitter end, and often took it out on me because he resented needing help. He couldn’t manage living alone in his five-bedroom home in Richmond. I was always frantic when I couldn’t get hold of him. I’d drop everything to drive over – often grabbing both my sleeping children, who got used to one emergency after another.

I eventually found him live-in carers to ease the pressure, at great expense to him.

He was lucky to be able to afford it. But even then, I was on call for all the constant medical emergencies, advocating for him in hospitals and during GP appointments, and dealing with his increasing demands. He’d ask me for ridiculous things like goose fat and mango jam. I was his daughter and a PA. We’d done a role reversal. I was now a parent to my parent. In the end, he moved in with me, and my flat was decked out with rails and recliner chairs and was littered with medication and visiting GPs and rapid response teams.

A study by UCL researchers, published in Public Health earlier this year, revealed that sandwich carers experienced a significant decline in mental health – especially those dedicating over 20 hours per week to caregiving – compared with non-sandwich carers. There are also financial pressures; around 53 per cent of sandwich carers report being unable to work at all or as much as they would like.

Over the last 40 years, the number of sandwich carers has risen dramatically, too, due to longer life expectancy and women having children later in life – as was the case for me.

Another study published by The Journals of Gerontology in 2024 found that people in their sixties and seventies experience greater health infirmity now than previous generations of the same age – putting more pressure on the sandwich carer.

I was lucky not to be part of the four-generation “club sandwich” – in which those in their forties to sixties find themselves caring for their children, parents and grandparents (or those in their twenties to forties in the same boat).

Caring for parents causes resentment in families. It tends to be one member doing it all. And it’s a challenging task, something only those who have done it can understand. It feels like a physical and emotional marathon. I was pulled in all directions. I look back, and I don’t know how I did it.

That last evening, the night my dad died, we sat opposite each other in his bedroom. He kept looking at me and smiling and then looking down. I think he knew he was leaving the world, although I didn’t, and he wanted me to know he was happy. It might not have been perfect – I got frustrated and he had his bad days – but I had made a promise. I told him I would do everything in my power to keep him out of a care home. And I did.