Inside MLB’s process of authenticating game-used items

When Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Roki Sasaki took the mound against the Chicago Cubs in Tokyo on Wednesday, he did so wearing an MLB debut patch on the left sleeve of his jersey. After his start, when leaving the game and coming off the field, the MLB authentication team said it would immediately remove the debut patch, authenticate it and place a hologram sticker on it.

The patch later will be embedded into Sasaki’s one-of-one numbered Topps Chrome Update Rookie Debut Patch Autograph Card for collectors to covet, chase and ultimately pull.

For fans of the sport, collectors and Sasaki, the moment is one that MLB wants to recognize and preserve for future generations. It’s also important for MLB’s authenticators, the team responsible for collecting, authenticating and cataloging the items that come off the field and become memorabilia.

“This is a sport that is about history,” said Michael Posner, head of MLB’s authentication team. “Recording that history properly and knowing, ‘This is the ball, the base, the bat,’ that’s what we’re doing. We’re protecting that history.”

In addition to the debut patch, which MLB started using in 2023, Posner said MLB authenticators also will collect the pitching rubber, home plate, baseballs, jerseys, locker tags and lineup cards in Tokyo for auction and to be cut up for Topps products.

Posner’s team has painstakingly collated baseball history since 2001. In the late 1990s, San Diego Padres star Tony Gwynn didn’t recognize his signature on signed merchandise being sold around Qualcomm Stadium. Even at Gwynn’s home ballpark, there were forgeries.

“When Tony pointed it out, everyone kind of looked at each other, like, ‘Oh, this is a problem,'” Posner said. He said the FBI got involved, and that many of the autographs on the market at that time were deemed fake.

“The idea of the program was born at that point,” Posner said.

Posner’s team has since authenticated more than 10.5 million items thanks to a team of roughly 250 authenticators, all current or former law enforcement. Home run balls are rarely authenticated. An MLB source said fewer than 30 ever, including Shohei Ohtani‘s highly sought-after 50/50 home run ball, which sold for a record $4.39 million last year.

When teams reported for spring training last month, Posner’s team did, too. It’s one of their busiest times of the year, with more than 100,000 items authenticated with hologram stickers. Normally, 90% of their work this time of year is witnessing teams’ community relations groups autograph sessions — for in-season fundraisers or charity events where authenticated items drive up dollars raised — and MLB licensees like Fanatics and MLB Alumni who have autograph deals with players.

“Everyone knows they’re going to be there from X to Y date, so they ship a bunch of stuff down, knock out a bunch of players,” Posner said. “If a fan goes online to the MLB.com shop and they buy an authenticated autograph of a player, odds are they’ll see a date corresponding with a spring training date.”

But this year, Posner’s team used spring training as a test run for applying a new system with more consistent methods to record information and guide authenticators through data entry. He said MLB wants fans to have a better understanding of the data being logged and conveyed — like ensuring that a base is described in New York the same as it is described in Minnesota or any other MLB location.

Posner said MLB’s use of the pitch clock starting in 2023 meant authenticators had less natural time between each pitch to log information, so the new system, which will be used in the 2025 season, will buy them more time. Posner, whose father was in the Air Force, notes a pertinent analogy: “Now the pilot isn’t taking his eyes off the sky.”

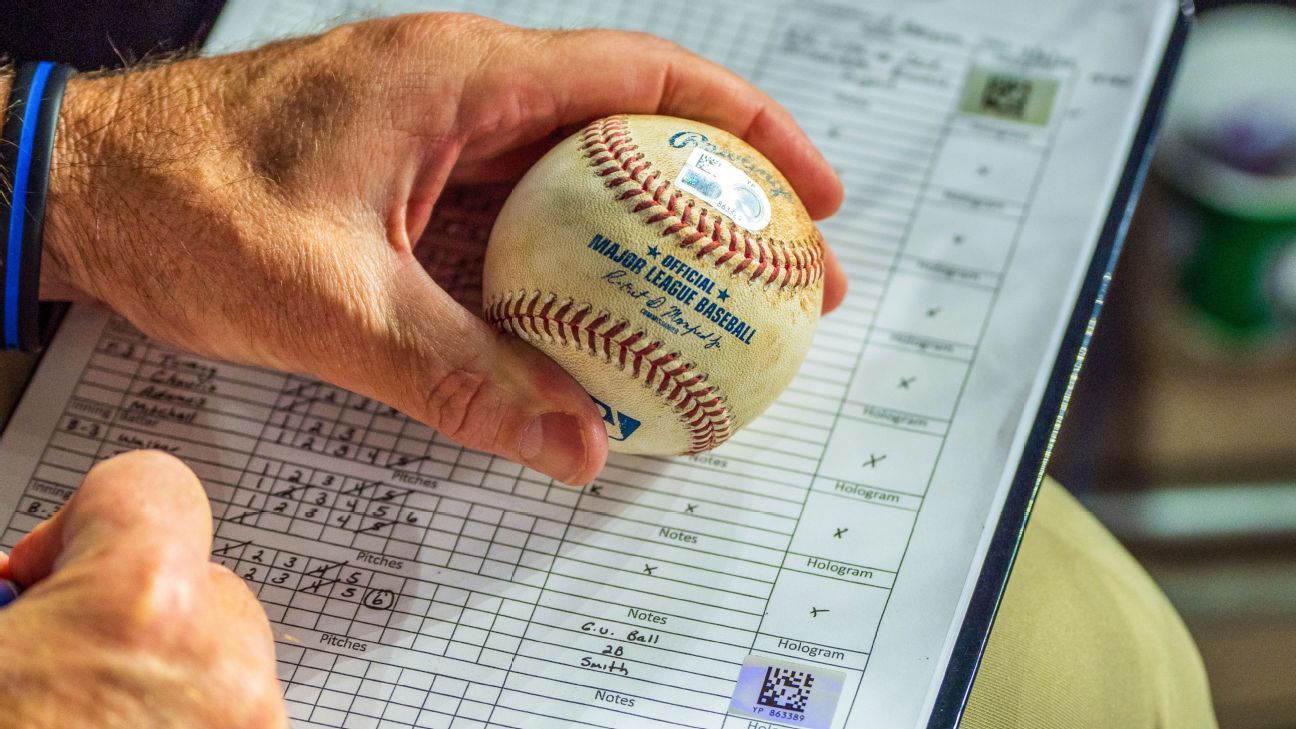

BENEATH YANKEE STADIUM’S visiting dugout before Game 4 of the 2024 World Series, surrounded by the rakes and shovels that manicure its infield, Posner ran through a list of items his team collects, authenticates and sends to Topps, which cuts up the items and inserts swatches into trading cards.

“Base on the field from Freddie [Freeman’s] home run in the 10th from Game 1 … pitches thrown by Yamamoto,” he said. “… base from the third inning of Game 2 … couple pitches thrown by Buehler from last night,” he said.

At one point, three eager grounds crew members sprinted up the dugout stairs and returned with auburn-flecked bases. A waiting authenticator — regular-season games have two, but there are five at Game 4 — with a roll of hologram stickers in hand certifies them and logs their data. Because of the game’s gravity — a potential Dodgers sweep didn’t materialize — bases were switched out after the second and fifth innings.

Posner’s team had just delivered Game 3 items to a nearby warehouse, which is a secure storage area in the basement that “only five people” can access.

The tamper-proof, self-destroying hologram sticker is from cybersecurity company OpSec. Attempts to remove it leave permanent marks behind. Posner said players have become aware of the importance and monetary value of authentication, and some even get items verified midgame.

“Miguel Cabrera was good at getting stuff authenticated,” he said. “Obviously this is a Hall of Famer — 3,000 hits, 500 home runs — so he understood, ‘Hey, there’s a lot of records I’m setting, a lot of personal milestones.‘ So if he hit a home run with a bat, the bat boy would bring it right to the authenticator in the dugout.”

Core groups of six or seven authenticators in cities throughout the season build rapport with players. With 15 regular-season games a night, and a large portion of authenticators’ responsibilities involving pitch tracking, the numbers can be dizzying. Ball boys deliver balls in or near a dugout, authenticators tag them, log the tracking data — pitch type, exit velocity, count, etc. — and turn in buckets of balls every few innings.

Posner’s team authenticated baseballs, all the bases and jerseys used in Game 4 of the World Series, the locker tags, on-deck circles, pitching rubber, lineup cards, cleats and batting helmets for both teams. During batting practice, Posner pulled Los Angeles utility man Tommy Edman’s batting helmet out of its cubby, revealing a hologram between the crown’s internal padding.

“This was used for all three games of the World Series so far, authenticated in L.A., updated twice by two different authenticators,” Posner said, scanning the hologram’s data. “We keep adding the use to the hologram, all the authenticators’ data gets entered within 24 hours of the game concluding.”

Authenticators will place hologram stickers on bottles of dirt, a lucrative enterprise for MLB. Topps, whose main cutting facilities are in Texas and Maryland, has embedded confetti, cornstalks from the Iowa-based Field of Dreams series and pieces of the Green Monster into cards.

“If it’s come through a ballpark and is part of the history of the sport,” Posner said, “we’ve authenticated it at some point.”

There’s not a call for résumés. MLB looks for candidates whose duties include games and autograph events requiring witnesses.

“We look for the best people we can find that understand this is a witness-based program,” Posner said.

When catcher Will Smith nabbed the final strike from Walker Buehler the following night, Posner’s team mobilized to place a hologram sticker on the ball.

Smith said the ball wasn’t his to keep, that he was going to give it to Buehler. Smith, Buehler and the Dodgers have put the ball up for auction, with proceeds from the sale going to relief efforts following the fires in Los Angeles.

SECURITY IN THE collectibles industry is a priority for leagues, as well as fans and collectors. The industry, valued at roughly $30 billion, has seen its share of alleged fraud. A spokesperson from the NFL, which has its own auction site, said the league strives “to offer auction items that are direct from the applicable athlete, team or league and come with a letter of authenticity certifying as to game use.” The NFL uses third-party authenticators like PSA, and photo-matching, and relies on club equipment managers to confirm game-used/non-game-used items sent to the league. The NBA doesn’t employ in-person authenticators, but its game-worn partner, Sotheby’s, uses MeiGray for photo-matching. Ultimately, guaranteed authenticity falls to documented provenance and chain of custody.

Around the turn of the century, card companies like Upper Deck, Fleer and Topps started embedding game-used memorabilia into cards. Topps’ 2000 Stadium Autograph Relic cards, which included a swatch of base from a player’s home stadium and the player’s autograph, marked their first entry into the space.

“The inception of the relic card was to bring the fan closer to the moment,” said Clay Luraschi, Topps’ senior vice president of product. “You want [fans] to look at that card 25 years from now and have it still mean something to them.”

Posner said there’s a balance between which items are MLB’s, which items go to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, and which items go to Topps. It’s an art, not a science.

“For an event like the World Series, we spend a lot of time talking to people ahead of time,” he said. “There’s something that’ll happen in a game and all three will say, ‘We’d like to get this thing.’ Someone’s going to come away disappointed if you’re dealing with a one-of-one item. We’ve had winners and losers on things, and people just have to deal with it.”

World Series bases, which are processed and embedded into cards in a matter of weeks, have become a Topps Now staple. The 2024 World Series Champions 15-Card Dodgers set, which didn’t include the base-embedded cards, was available for $60. It included parallels and autographs from Ohtani, Yamamoto, Max Muncy, Buehler, Teoscar Hernandez, Edman and Smith. More than 37,802 were sold in eight days. The Topps Now set featuring World Series bases went up for 24 hours this past Halloween, for $375 a pop, with a print run of 885.

“You’ve seen pieces of the Green Monster, we’ve done stadium seats, cornstalks, the MLB debut patches,” Luraschi said, referencing the first memorabilia patch specifically made for sports trading cards. “We’ll continue to evolve what we put into a trading card.”

Depending on who owns an item — batting gloves and cleats belong to players, jerseys belong to clubs — the hierarchy on items comes down to their importance to MLB history.

“If the Hall of Fame makes a call and they’re looking for a piece, they’re going to take priority,” Luraschi said, laughing, “but we get our fair share.”

Posner said it’s collaborative. If there’s a milestone and a player wants a keepsake, they get to keep things, too.

JON SHESTAKOFSKY, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s vice president of communications and education, was on the clock for Game 1 of the 2024 World Series. It was the bottom of the 10th, bases loaded, a one-run game, and the Dodgers were down to their last out against the Yankees. Freeman was nursing a right ankle injury; he’d also have to hit it out of the infield to bring a run home. Shestakofsky knew his boss, Josh Rawitch, president of the Hall of Fame, needed something of Freeman’s from Game 1 to mark that history.

“Jon went to Freddie after that game,” Rawitch said. “We knew, even if the Dodgers hadn’t won the Series … we were going to want those spikes.”

Rawitch said Freeman was kind and happy to help, anything they needed. In a matter of minutes following the game, he’d promised Shestakofsky and the Hall of Fame his kicks. Just one problem: Freeman didn’t have another pair for Game 2. He needed to hold on to them just a little longer.

Two weeks after Smith handed the final out to Buehler, Freeman’s cleats arrived in Cooperstown. So, too, did Mookie Betts’ batting gloves, Buehler’s glove he wore during the final out, Edman’s batting helmet that Posner scanned in New York, Clayton Kershaw’s champagne-soaked championship hat and Smith’s chest protector and cap.

“I watched him take those off and hand them to me,” Rawitch said, “Anthony Banda, who pitched in all four Dodger wins; a left-hander wearing No. 43, with the 34 patch for Fernando Valenzuela on his sleeve, tying together that storyline.”

Rawitch’s staff tends to 40,000 three-dimensional artifacts, 3 million archived physical documents and 14,000 hours of video and audio archives — 90% of which, by Rawitch’s estimate, are kept in climate-controlled vaults beneath Main Street in Cooperstown.

“If we go to a guy and ask to bring their jersey to Cooperstown and they offer a hat, helmet or spikes, we’re more than happy to work with them,” Rawitch said. “But 95% of the time, players are more than willing to give. They recognize, first of all, it’ll never be sold; it’s for the sake of preserving the history of the game.”

When Buehler was asked to donate his glove, he tried to give his cleats and hat, too.

“I said, ‘Well, we want you to also be able to enjoy this,'” Rawitch said.

The Hall of Fame houses the nostalgia in two temperature-, light- and humidity-controlled vaults in the basement. The Doubleday baseball is still on display, and every era since the Civil War is represented, curated by full-time collections and archives departments that still bring in 200 to 300 new artifacts a year. Rawitch said that to display all the items would require a museum five times the size they have and would require much more time of patrons.

Last summer, Rawitch hosted George Sisler’s great-grandson, who had never met Sisler. On a recent tour, Rawitch said a patron offhandedly mentioned that their grandfather was a Yankees Stadium usher who had donated an usher’s cap.

“I knew exactly where it was and got it,” he said. “It becomes such an important thing for players to recognize and be comfortable with: They’re donating something that has monetary value, but the historical value is just as important.”

Marking history also means final out balls — of which Cooperstown boasts nine, including the first World Series in 1903 and 2004, when the Red Sox broke The Curse.

The Hall of Fame is a nonprofit — not owned or operated by Major League Baseball. And half the items that arrive every year are from an MLB, MILB field or otherwise professional moment and assessed by an internal accessions committee.

Sometimes they come in more unlikely ways. Ichiro Suzuki, who will be inducted in July after receiving 99.9% of the votes required, intends to donate his entire personal collection to Cooperstown.

Rawitch said that since MLB’s authentication program started in 2001, the large majority of items that have come in bear that authentication sticker.

“Everybody who works here has a deep respect for the history of the game,” he said. “It’s why this place exists — because the people who came before us have been taking that same approach for 85 years.”