Keir Starmer won power without a purpose. Now he risks squandering it | Rafael Behr

Upsetting backbench MPs is an occupational hazard for prime ministers. Government is an endless sequence of messy compromises. Incumbency is a drag on popularity. Poll ratings sink and nerves fray. Careers are thwarted. There are fewer ministerial jobs than ambitious candidates.

This is normal party discontentment. It grows over the course of a parliament, becoming critical at the point when rebel numbers threaten the leader’s majority. By that metric, Keir Starmer can afford to provoke a lot of dissatisfaction in the ranks. And, together with Rachel Reeves, he has.

The Labour mood in the aftermath of last week’s spring statement is bleak. Shrinking benefits in the name of fiscal rectitude was never going to go down well with MPs who spent years in opposition denouncing the Tories for that sort of thing. But the demoralising effect is greater for being cumulative. It is just over a month since Starmer raided the overseas aid budget to fund higher defence spending. Weeks earlier, Reeves landed Heathrow airport expansion on a party that would rather be striving for net zero.

Each time, Labour MPs are presented with a plausible force majeure justification – economic growth is the precondition for revenue to fund good causes; Vladimir Putin makes rearmament urgent; a welfare system marked by perverse incentives that steer people away from work needs reform. In isolation, any single unpalatable choice would be easier to swallow. As a multi-course meal, it turns the stomachs of MPs who feel they weren’t consulted on the menu.

Open defiance is still rare. Ruthless whipping encourages discipline. MPs newly elected in 2024 are reminded that they owe their seats to Starmer, although that line is wearing thin. Submissive gratitude isn’t what motivates people to enter parliament. Some with slim majorities, eyeing opinion polls gloomily, are already thinking about life post-politics.

Anxiety, tending towards despair, swells largely under the surface. It isn’t confined to any one faction. Downing Street would like to imagine that dissent springs only from a recalcitrant left, fomented by people who will never forgive Starmer for not being Jeremy Corbyn and then parlaying that distinction into a massive election victory.

That is one source of dissatisfaction, but far from the only one. The malaise afflicts young MPs who were handpicked for loyalty to Starmer, grandees of New Labour vintage and every flavour of soft-left social democrat in the middle.

It is hard to get the full measure of a syndrome that is expressed in exasperated whispers through gritted teeth and pained rolling of eyes. There are plenty of Labour MPs, including cabinet ministers, who dutifully cheer the prime minister in the Commons, then seethe with frustration in the adjoining corridors.

Different wings of the party have rival policy prescriptions, but the core complaint is the same. It is the lack of discernible strategic purpose. There are “milestones”, but on the road to where? There are “missions”, but how will Britain be different, feel better, once they are accomplished?

Loyal defenders of the government point out, fairly, that these are still early days in an exceptionally tough climate. There were no shortcuts back to prosperity, given the abject state of things left by the Tories. The performance of a new administration in its first year is not a reliable guide to its future prospects. In early 1981, for example, it looked feasible that mass unemployment and social unrest would sink Margaret Thatcher. She stayed comfortably afloat through two subsequent elections.

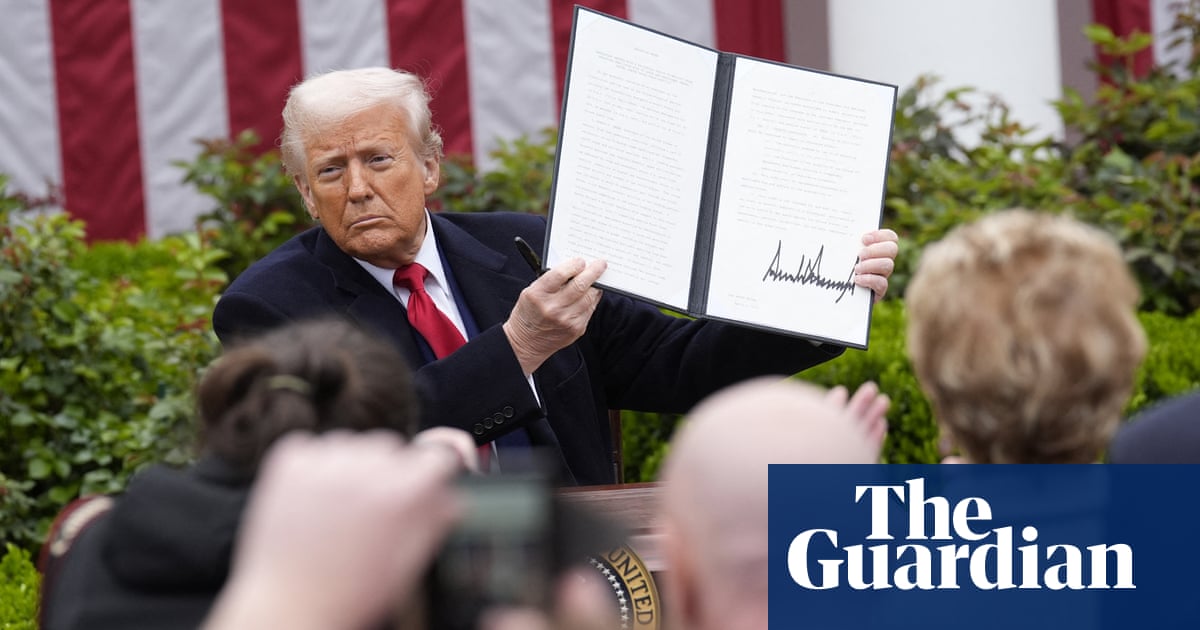

One elaboration of that comparison configures Donald Trump’s upending of the global order, and Starmer’s seizure of the diplomatic initiative in support of Ukraine, as a pivotal moment in the prime minister’s national standing; a boost in stature much as Thatcher’s prestige soared after the Falklands war.

That is a stretch. Still, there is some polling evidence that the Labour leader’s sure-footedness on the international stage has helped his domestic reputation. And, come the next general election, Starmer doesn’t have to be cherished as a visionary prime minister if enough voters continue to think that he is the safer choice than any of the alternatives.

That doesn’t reassure MPs who crave a nobler purpose, and a less shrivelled message, than just keeping the Tories out. Also, that imperative has dwindling purchase on the growing cohort of voters who see Labour and Tories as interchangeable and equally contemptible.

Starmer’s struggle for definition predates his arrival in No 10. This week he will mark his fifth anniversary as party leader, and throughout that time his successes have been a function more of the people he wasn’t than by things he wanted to achieve. He wasn’t Corbyn, for a start. He was the antithesis to Boris Johnson; the antidote to Liz Truss; the available alternative to Rishi Sunak. Now he is good at being unlike Trump – a positive attribute but a passive one.

A leader whose outline can only be drawn with reference to other, worse politicians ends up appearing to voters only in silhouette, without colour or humanising contour.

The government’s agenda is also circumscribed by decisions made in opposition, defining the project by things it was not. Labour’s pre-election fiscal policy was drafted in fear of being cast by the Tories as profligate with public money and wedded to high taxes.

As a result, while Reeves is the nominal author of her budget and forthcoming spending review, she has to fit them in impossibly narrow margins. The lines on the page were ruled for her by Jeremy Hunt as a deliberate act of sabotage when he knew he would soon be vacating the chancellor’s desk.

Even if current growth-boosting policies work, the benefits won’t accrue fast enough to compensate for deteriorating services. Budget cuts also save less money than advertised when they exacerbate social deprivation, increasing pressure on other services.

Absent some unforeseen cash windfall, a revision of tax policy is inevitable if the government is serious about rehabilitating the public realm. Abler communicators than Reeves and Starmer would have started narrating their way out of that particular corner already. Trump’s tsunami of tariffs would be a valid reason to declare previous commitments void.

It is especially unfortunate that the prime minister and the chancellor share the same deficiency in this regard. They speak as if every phrase has been scanned for originality, frisked for authenticity and prevented from carrying any unprocessed feelings from the heart through the maximum security gates of their mouths. They are both politicians who reached the top by winning internal battles, not public arguments.

This is something even their close allies concede is a problem, although they are obliged to downplay its significance. It isn’t going to change. It didn’t stop Labour winning before and, less than a year since the election, it is far too early to know whether it will win again.

But when, after five years, the leader is still defined by things he is not, Labour MPs are justified in worrying that their time in government is being squandered and they will end up being remembered for all the things they failed to do.