Ming Fay, Who Made Magical Sculptures of the Natural World, Dies at 82

Anyone who enters the New York City subway at Delancey Street is bound to notice the striking mosaic portraits of fish heads inlaid in the station’s white-tile walls. Bordered in gold, with shades of pink, purple and blue, they give their iridescent subjects all the majesty of a king or queen on an ancient coin, but with a air of whimsy.

Commuters who continue downstairs to board the F train will discover a mosaic of three enormous shad covering one wall and a gracious, spreading cherry orchard on the wall across the tracks.

Finished in 2004, these mosaics are probably the most visible public artwork of the sculptor Ming Fay, who died on Feb. 23 at home in Manhattan. He was 82.

His son, Parker Fay, who confirmed the death, said the cause was a cardiac event.

Mr. Fay’s public art took its inspiration from a location’s history and natural surroundings. His first installation, at Public School 7Q in Elmhurst, Queens, in 1995, included an enormous bronze gate shaped like an elm leaf. For the Whitehall ferry terminal in downtown Manhattan, he designed canoe-shaped granite benches to pay tribute to the Native Americans who once crossed from Staten Island to Manhattan by boat.

The Delancey Street shad were a nod to an indigenous fish whose populations were dwindling and to Brooklyn-bound subway riders soon to be passing underwater themselves. Mr. Fay didn’t generally work in mosaic — these, his first, were assembled by a team of specialists.

Otherwise, the shad were typical of his practice: an easily overlooked feature of the natural world that he made both magical and unmissable by enlarging it to human scale.

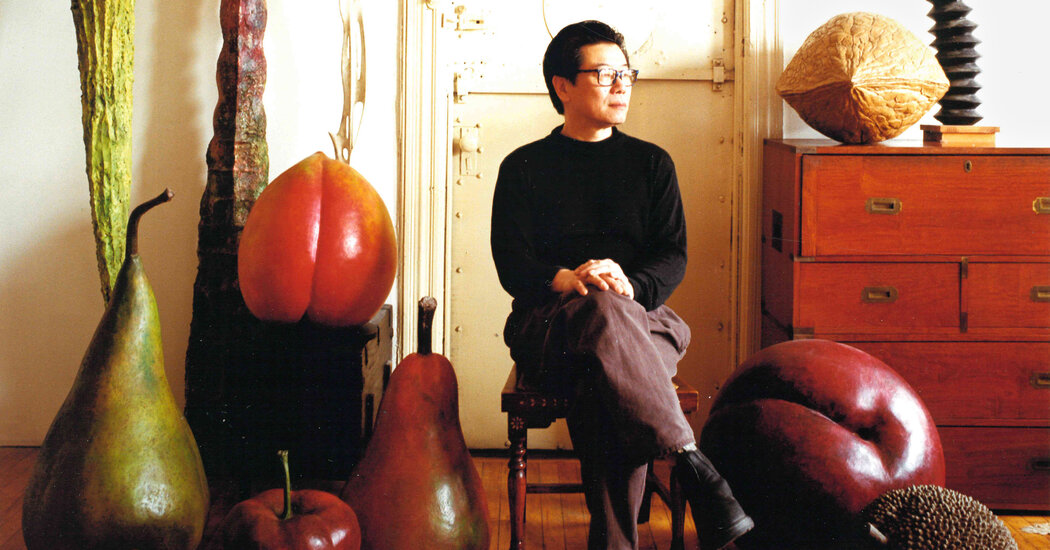

For more than 50 years — in a series of studios in Chinatown, in Manhattan; in Dumbo, Brooklyn; in Jersey City, N.J.; and in his home, which was high above the Strand bookstore near Union Square in Manhattan, until he moved farther down Broadway in 2013 — Mr. Fay made giant, unnervingly realistic fruits, vegetables, seashells, wishbones and semi-imagined “hybrid” objects with a signature technique of painted papier-mâché over steel armature.

In his work, Western techniques and influences met Chinese symbolism and an urbanite’s somewhat romantic view of the natural world. Many of the pieces were inspired by a vast collection of seeds, nuts and other natural objects that he was given or had picked up over the years.

Writing for The New York Times in 1991, Michael Brenson described Mr. Fay’s papier-mâché wishbones, walnuts and conchs as “distant relatives of the giant fruits of Claes Oldenburg, the giant shells of Tony Cragg and the organic figural abstractions of Robert Therrien.”

But they weren’t only that. In a 1998 exhibition brochure, the poet and critic John Yau proposed that there was something revolutionary in the cross-cultural combination of ingredients.

“Instead of collapsing the barrier between art and culture, as Flavin, Warhol and others have done,” Mr. Yau wrote, “Fay, through his construction of large-scale sculptures of fruits, seed pods and vegetables, reminds us that nature, rather than culture, is what we all finally inhabit.”

Ming Gi Fay was born on Feb. 2, 1943, in Shanghai, to Ting Gi Ying and Rex Fay, both of whom were artists. After relocating to Hong Kong in 1952, his father worked as a set designer and his mother taught painting. She also taught her son to make paper lanterns and kites.

In addition to his son, who manages his studio, Mr. Fay is survived by his sister, Mun Fay, a toy designer, and his partner, Bian Hong, an artist. His marriage to Pui Lee Chang ended in divorce.

Speaking to WP, the magazine of William Paterson University, where he was a tenured professor of sculpture, Mr. Fay recalled that his interest in art was awakened while he was confined to bed as a child, during a yearlong recovery from appendicitis.

“The only things I had to look at were picture books,” he said. “I read everything from master painting books to comic books during that time. That was my spiritual healing.”

When he was 18, Mr. Fay was offered a full scholarship to Columbus College of Art & Design in Ohio, where he was one of the first Asian students. He had chosen design, at his father’s urging, as a more practical path than fine art, and later credited that training with some of his success in landing public commissions.

But before he finished his degree, he fell in love with sculpture and transferred to the Kansas City Art Institute, where he made large, geometric works in steel and earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1967. He followed this with a Master of Fine Arts at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1970.

In 1972, Mr. Fay moved to New York, landing first in a Canal Street loft near Chinatown markets full of interesting produce. It was then that he switched from geometric steel to figurative papier-mâché, partly for practical reasons.

“In my early New York days when I was living and working in a loft with very limited resources for sculpture materials,” he later recalled, “a pile of Sunday New York Times inspired me to try to make papier-mâché sculptures.”

The first one he made was a giant pear, a traditional Chinese symbol of prosperity. Over the years, he also worked with spray foam, wax and ceramics, and painted. Later, he moved from making individual objects to creating entire garden- or junglelike environments.

Finding community in New York was a struggle, and opportunities for Asian artists were few. Eventually, Mr. Fay became friends with other artists — among them, Tehching Hsieh, Chakaia Booker and David Diao — and began holding raucous dinner parties. In 1982, he and half a dozen other artists of Chinese descent formed the Epoxy Art Group, which made multipart research-based political work, including “Thirty-Six Tactics” (1987) and “The Decolonization of Hong Kong” (1992), using news clippings and Xerox machines.

In addition to teaching at William Paterson, Mr. Fay was a visiting professor at the Rinehart School of Sculpture at the Maryland Institute College of Art. He also took a semester-long break from his own M.F.A. program to teach at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His work was collected by the Brooklyn Museum and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin, among other institutions, and was shown in Taiwan, Hong Kong and mainland China, and around the United States. In New York, he was represented by Alisan Fine Arts.

Speaking to The Times in 2012, Mr. Fay described his unusual artistic path as a response to his environment and as a way of healing himself and others.

“I am an urban person, a city boy,” he said. “In the Midwest, there had been an abundance of nature. In New York, I felt the isolation and divide from nature. At the time I was looking for new work to do.”

He added: “I found nature as an interesting place to go into. It became a kind of calling.”