On Appalachia Borealis, Phil Cook Blends Piano and Birdsong

Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, perhaps a touch ironically, “You must hear the bird’s song without attempting to render it into nouns and verbs…Cannot we let the morning be?” Surely the poet and essayist wouldn’t have objected to distilling a few chirps and warbles into music, as Phil Cook does on Appalachia Borealis, a singular new piano album inspired by the winged residents of the North Carolina Piedmont.

The Durham-based musician followed in the transcendentalists’ footsteps in 2022 when he went to the woods of Orange County, North Carolina, for a musical and personal reset. A multi-instrumentalist known for cofounding the band Megafaun and collaborating with the likes of Waxahatchee, the Indigo Girls, the Blind Boys of Alabama, and Hiss Golden Messenger, Cook was coming off a period of growth and upheaval: He’d recently turned forty and rededicated himself to the piano. He’d weathered the pandemic, finding respite in local nature preserves with his two young sons. And he was going through a divorce, a process that he says left him “broken wide open.”

When friends offered to rent out their small farmhouse on the edge of a forest, Cook found himself living alone for the first time in his life. “It’s quiet and there are good sunsets, there’s a good front porch, and I’ve got a piano,” he recalls. At first his morning sessions at the instrument were purely meditative, but over time, as unfiltered birdsong flowed through the open windows, the sounds in the room mingled into something more.

Appalachia Borealis follows Cook’s first solo piano album, 2021’s All These Years, but it’s an entirely different listening experience. At the advice of gospel pianist Chuckey Robinson, Cook backed off the sustain pedal, an adjustment that lends intimacy and clarity to the music. Cook’s childhood friend, Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, added a producer’s touch, pumping different birdsongs into Cook’s headphones as he played and sometimes routing the notes through a reverb chamber at April Base, his studio in the pair’s home state of Wisconsin.

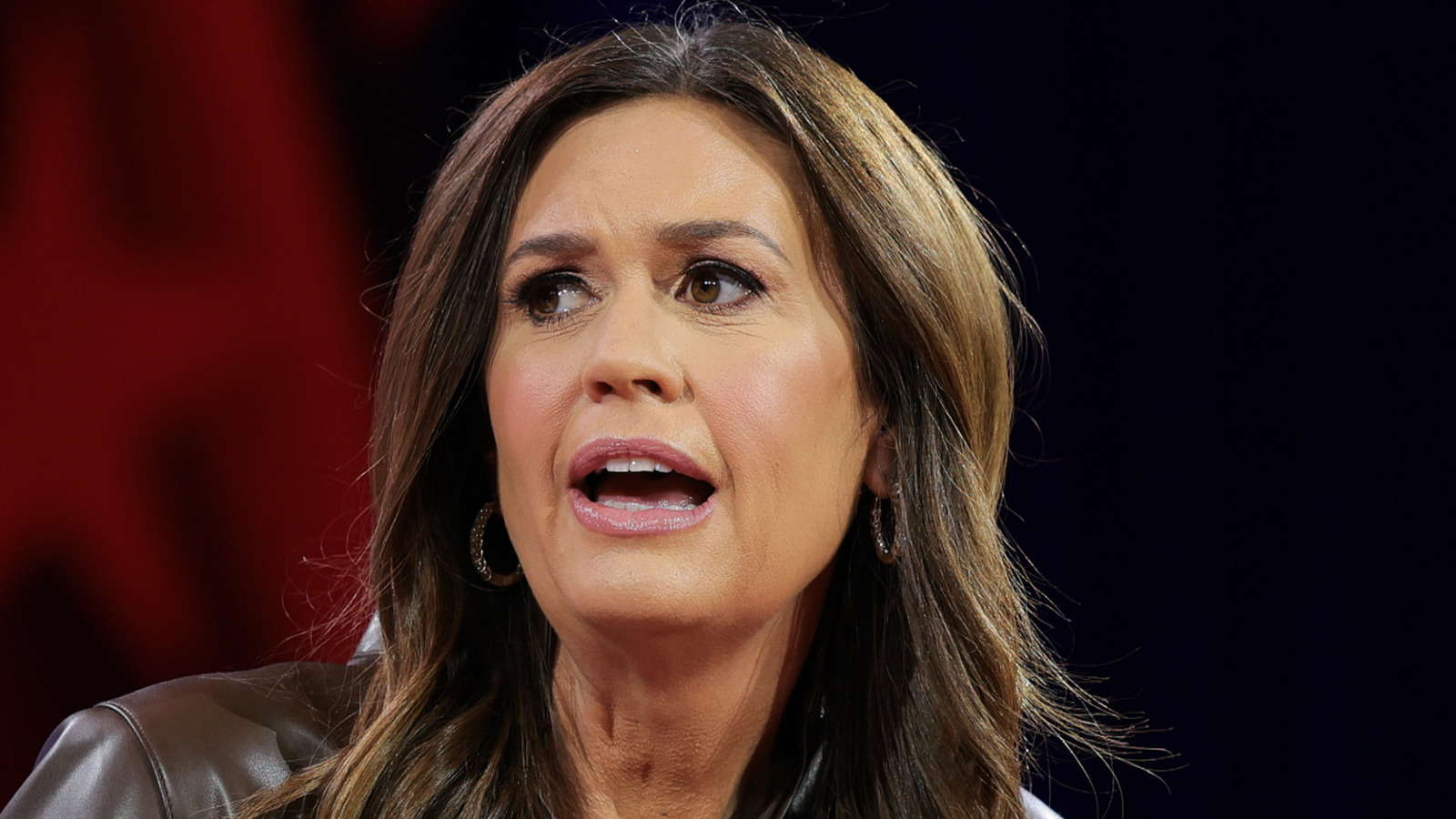

Cook in the studio with Justin Vernon.

And then there are the birds themselves, who make direct appearances on some tracks, like the gently bluesy “Thrush Song.” Other times they serve as a metaphor, as in the pulsing, joyful “Buffalo,” whose melody springs forth “as though a hatchling from an egg,” according to the album notes.

Recordings of birds (and other multimedia) will also accompany Cook during his tour, which kicks off this weekend at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee. “I’m really looking forward to getting back on the road for the first time in five years and meeting people again with, I think, a lot more under my belt—a lot better self-understanding, and music that is the most personal I’ve made,” he says.

Read about Cook’s journey in his own words below, and listen to the album here.

I hear you’re a collector of voice notes.

I looked last night, and I have 1,800 voice memos on my phone. It’s a really accessible journal for me to capture something really quickly, and I’ll put it at a piano or a guitar if I write something. But then I started using it for little interviews or when I’m with my kids; my son had a speech impediment that only three-year-olds and four-year-olds have and then they grow out of it, and I would just record him telling stories.

You can take a video—that’s the default for most people—but I like listening back because you don’t have everything given to you. You just have the voice. And it transports me in a different way.

When did you know your bird recordings were the basis of your next musical project?

One spring morning my windowsill was cracked at the head of my bed, and there was a willow tree right outside. There was a mockingbird perched right there, and it was really going for it. In my waking stupor I just put my phone on the windowsill and started recording. And that day I came to my studio, and for some reason I put the voice memo in my headphones on a loop—I’m just warming up with all my scales, but the effect on my body was like, “Wow, I’m in the woods right now.” All of my guards and expectations dropped away. As soon as I got done warming up, I wrote three songs right away.

How do you envision people listening to this album? Do they have the window open and a breeze blowing in?

When I made my first piano record, I had no way to anticipate how people were going to react to these meditative piano recordings. I began to get these very personal letters in the mail, and people would share where the record had been with them. The common theme, which really floored me, was these rites of passage—having the music in the room when their family member passed away, or when their baby was born, or walking down the aisle for a wedding. Musician friends that I didn’t know very well would pull me aside and share things like, “I have terrible flight anxiety, and for some reason when I put on your record I’m okay.”

I do feel like instrumental music, and music that is more meditative, has a really relevant place right now. Having no words is important because people have a lot of thoughts in their head. So I hope the record can be a companion to people as they navigate their day; I picture it in people’s headphones when they’re out in the world, or when they’re alone. It’s not a record you put on at a party, I’m going to tell you that right now.

The title song, Appalachia Borealis, features a bird that’s not found in the Appalachians—the loon—and it almost sounds like it’s calling back to you. Am I reading too much into that?

You’re reading it exactly right. Where I grew up in Northern Wisconsin, the aurora borealis was part of culture. The title kind of merges these two beautiful ideas: I love Appalachia and I love the aura borealis, but they’re just concepts of bridging my two homes together.

The most sacred place in my life is a cabin my family has had for 115 years in Northern Wisconsin. In the early morning, at five or six a.m., the lake is glass and the loons will call into the total silence and it’ll echo into other lakes, and it’s the most haunting, beautiful, stirring sound. So that song is really a love letter and a longing. Wherever I am, I long for the other place.

Besides the loon, do you have a favorite bird call?

I’ve become so fascinated with northern mockingbirds; they’re ubiquitous around Durham. I looked into it, and mockingbirds live about eight years in the wild, and in that time they mimic everything they hear, including car horns. They’ll put it into this reel that’s like every recording they’ve ever made, and they’ll have up to two hundred in their lifetime. So when you hear a mockingbird calling, it’s doing its recitations. There’s a mockingbird in me. I absorb all these things in my life and spit them back out again for other people.