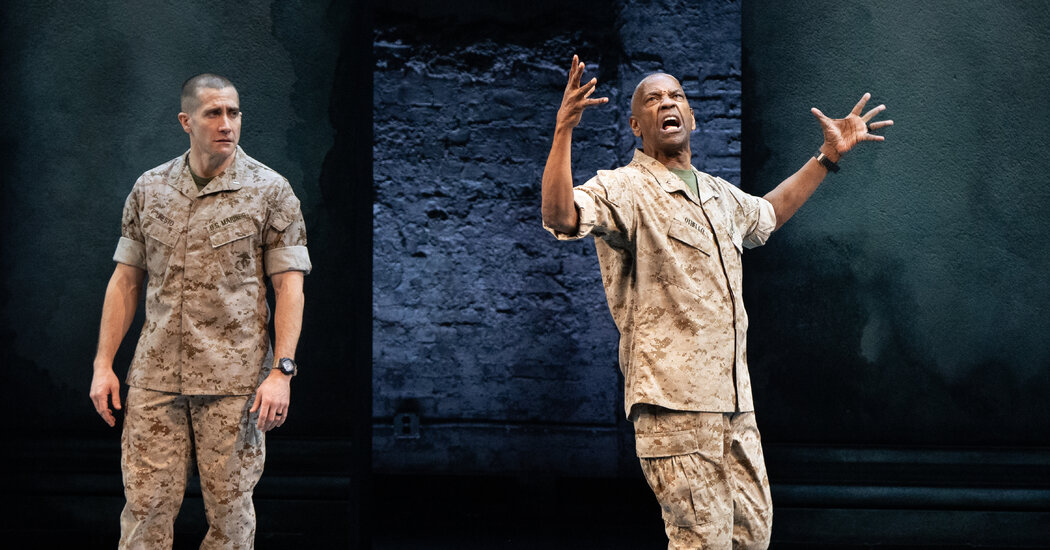

‘Othello’ Review: Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal Are Prey and Predator

Just moments earlier, he was an infatuated new husband, and she his “gentle love.” Now, in Act III, Scene 3 of “Othello,” he vows to kill her.

What has happened? Why does Othello, the great Black general, the savior of Venice in a war with the Ottomans, resolve to murder Desdemona, the pearl of the white aristocracy he has won at great risk?

The scene in which this strange alteration occurs is one of the most gripping, baffling episodes in Shakespeare, and it remains so in the starry Broadway revival of “Othello” that opened on Sunday at the Ethel Barrymore Theater.

We can be grateful for that — and yet, in Denzel Washington’s commanding performance, what’s especially gripping is perhaps too baffling. As in his many movies, he leads with action, giving us a general whose psychology is as obscure to us as it is to him. Speaking very fast, with a slight mid-Atlantic accent, and stiffened by his ramrod military bearing, he betrays little evidence of the sorrows and injuries that moved Desdemona when he wooed her. Speed and decisiveness (“to be once in doubt is once to be resolved”) seem to matter more than emotion.

Usually the obscure one is Othello’s ensign, Iago. Though Shakespeare provides many possible reasons he might have wanted to poison his commander with lies about Desdemona, awakening the famous green-eyed monster of jealousy, we are typically still in the dark at the end, when the cur is sent to his punishment. “I am not what I am” is his paradoxical, irreducible credo. Then what is he?

Yet in a fascinating reversal, this “Othello” offers an Iago far more legible than his master. Jake Gyllenhaal’s eely take, with a physical wiggle to match his moral one, is a little bit mad scientist, a little bit Travis Bickle. His blue eyes pierce the atmospheric murk as he tracks all possible routes to his goal, like a rat in a maze, in the process allowing us to see how a twisted man thinks. He is a calculator of grievance; havoc is the carefully tabulated result. He adds up.

The switched polarities are arresting to observe in Kenny Leon’s handsome and headlong modern-dress production. Othello enters that fateful scene fully sane and even lighthearted. He banters easily with Desdemona (Molly Osborne) and agrees to reconsider his harsh punishment of Cassio (Andrew Burnap), a lieutenant whose uncharacteristic roistering resulted in violence some nights before. “I will deny thee nothing,” he tells his wife uxoriously.

Then Iago enters. Purveying the lie that Cassio has slept with Desdemona and, somehow even worse, that he was seen to “wipe his beard” with the handkerchief Othello gave her, the ensign works his evil alchemy, flipping his master’s master switch in a moment. Henceforth Othello is only monstrous, and Washington makes an excellent monster. But he has not earlier and does not now offer gradations of character that would help connect the before to the after.

To be fair, Shakespeare doesn’t either. The possibility of a sympathetic racial interpretation of Othello’s rage is mostly voided by the evident racist glee of the writing. When, in Act I, Iago warns Desdemona’s father (Daniel Pearce, excellent) of the consequences of her marriage to a “Barbary horse,” what he adds is beyond hideous: “You’ll have your nephews” — meaning his grandchildren — “neigh to you.” Yet Othello never takes the bait or acknowledges prejudice except glancingly.

Nor does this production make hay of the play’s potential homoerotics. The fantasia Iago spins to convince Othello of Cassio’s betrayal — that, in his sleep, moaning for Desdemona, he “kissed me hard” then “laid his leg o’er my thigh” — can’t help but make a modern audience wonder. Does lust play any part in the ensign’s envy of the handsome lieutenant, who is also, in Burnap’s performance, so boyishly sympathetic?

Similarly sexually cloudy is Iago’s connection to Roderigo, usually a comic patsy but much more complex in Anthony Michael Lopez’s performance. When Iago urges him to cuckold Othello, it’s hard not to hear his reasoning — “thou dost thyself a pleasure, me a sport” — in reverse.

In any case, the possessiveness of love that in some men becomes paranoia is a theme that needs exploring in “Othello” or its engine will not turn over. After all, one thread of Iago’s rage is his belief, on no evidence, that he, too, was cuckolded — by Othello himself.

The large age difference between Washington, who is 70, and Osborne, who is 27, might have enhanced such an exploration, but the subject is ignored. (Iago is likewise aged up, to “six times seven” from “four times seven” years.) Indeed, Osborne’s Desdemona, though charming in speech and credible in affection, is also cosmopolitan and businesslike, hardly the maiden Shakespeare describes as “of spirit so still and quiet that her motion / Blushed at herself.”

These avoidances, and others, do little harm in themselves, but accumulate into a mist of confusion. Perhaps Leon’s decision to set the action “in the near future” (as a projection tells us at the start) is part of that problem, as we cannot discern how the shift from the presumable 1570s of the text, when a real war between Venice and the Ottomans was waged, is meant to influence our understanding.

The geographical setting is also vague. The collection of slab-like columns by Derek McLane, lit in sickly, sullen colors by Natasha Katz, could be anywhere. Though some uniforms marked “Polizia” suggest Venice, others feature U.S. flags, and Dede Ayite’s exceedingly well-cut civilian suits and Armani-style ensembles for Desdemona perhaps point more to Milan. Interstitial music includes American hip-hop and Andrea Bocelli in schmaltzy Europop mode.

In short, as I felt the production’s blunt force more and more, I grasped its aura and aims less and less.

“Othello,” unique among Shakespeare’s tragedies, is lean. (It’s even leaner in this production, thanks to some judicious cutting.) It has fewer major characters than most, and fewer sideshows. (Among the cuts: the annoying clown.) Its poetry is extraordinary. And though four principals die, all ultimately by Iago’s hand or influence, it does not tumble indiscriminately toward the blood bath. The deaths are specific and necessary to its themes.

Leon’s “Othello” gets all that, except the themes. A good enough bargain, I suppose — or would be, except that center orchestra tickets are selling for $921.

You could spend a lot less — or a lot more — to learn the sad truth “Othello” dramatizes: that those who choose to assume the best in people are most vulnerable to the worst. Innocence is ignorance, certainty a death wish. In a world (and on a stage) that loves not wisely but too well, Iago will always win.

Othello

Through June 8 at the Ethel Barrymore Theater, Manhattan; othellobway.com. Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes.