The Fed Isn’t Rushing to Save the Markets This Time

The notion that the Federal Reserve will rush in to rescue investors in a crisis has comforted investors for decades. But in the big market downturn induced by President Trump’s tariffs, no Fed rescue is in sight.

Jerome H. Powell, the Federal Reserve chair, made that clear on Friday. The tariffs are much “larger than expected,” he said, and their immense scale makes it especially important for the central bank to understand their economic effects before taking action.

“It is too soon to say what will be the appropriate path for monetary policy,” he said at a conference in Virginia.

In fact, I’d say, the likelihood of further market declines is much greater than the chance that the Fed will turn the markets around in the immediate future.

What U.S. stock investors have experienced until now is what’s known on Wall Street as a correction — a decline of 10 percent or more from a market peak. The correction doesn’t end, by this common definition, until the markets have turned around and that peak has been surpassed. For days, though, the market momentum has been almost entirely downward. So another dubious distinction is in sight: a bear market, which is a decline of at least 20 percent from a market top. For the S&P 500, which closed at 5,074.08 on Friday, down from its peak of 6,144.15 on Feb. 19, a bear market is already within shouting distance, a scant 2.6 percentage points away.

It would be lovely to be able to say that the stock market bottom is near, or that it has already been reached, Edward Yardeni, a veteran market watcher, said in a conversation on Friday.

“I’ve been pretty good at picking market bottoms, and I’m not shy about calling one when I see one,” he said. “But that usually has happened when the Fed has taken action. And right now, its pretty clear that Powell won’t be doing that.”

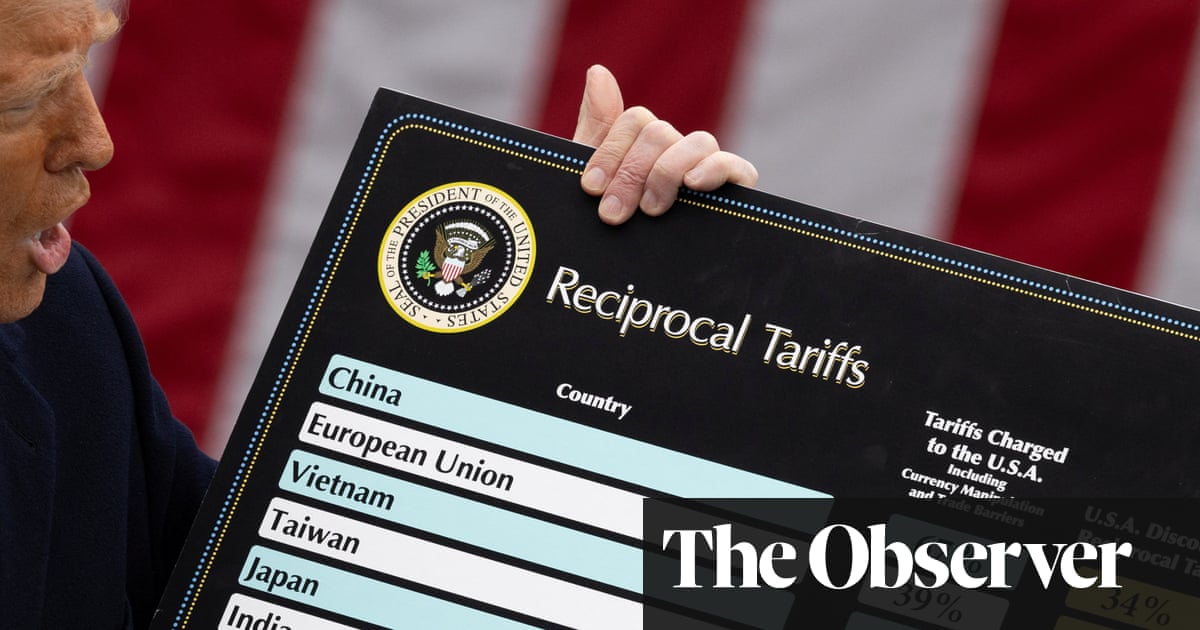

The Fed is holding back this time for good reasons. The impact of the sudden new range of tariffs imposed by the president — and the tit-for-tat tariffs announced on Friday by China that are likely to be followed by similar moves from a host of other countries — is far from clear.

But this much is certain. Tariffs are a tax, one that is likely to slow economic growth as well as raise prices. Those effects complicate the task of the Fed, which has a dual mandate: promoting full employment (and economic growth) and holding the rate of inflation down to a reasonable level.

With the Fed still battling inflation after the runaway surge in prices of 2022 and 2023, it is reluctant to lower interest rates when price increases in a range of goods could be just around the corner. And on Friday, the latest jobs report from the government showed that the economy in March remained reasonably strong. Employers added 228,000 jobs for the month, far more than anticipated, and while the unemployment rate rose slightly, to 4.2 percent from 4.1 percent, there were few signs of substantial weakness.

Given that backdrop, Mr. Powell seemed to be signaling that it would take an actual slowdown, with substantial job declines, to justify rate cuts under current circumstances. Consumer confidence has declined, and an Economic Policy Uncertainty Index that is closely watched by economists and business executives has soared. But concrete data isn’t here yet. If they’re not rolled back, the tariffs are likely to take a while to result in widespread layoffs — and without strong evidence of a slowdown, the Fed may be reluctant to act.

Yet the Fed has already come under pressure from President Trump to lower interest rates. This is the “PERFECT time” for a Fed rate cut, he said on the Truth Social media platform on Friday, shortly before Mr. Powell’s speech. Maintaining Fed independence is important in the markets, and there was no indication that this overt presidential pressure had any effect on Mr. Powell’s staunch resolve to bide his time, and to lower interest rates only when and if the Fed decided it was time to do so.

So investors may need to be very patient, and to hope that changes in tariff policy occur rapidly enough in Washington to turn the markets around and, more important, avert a recession. Recessions are typically associated with wide-ranging job losses, and they cause immense hardship in the real world as well as in financial markets.

Recessions usually make bear markets much worse, Ned Davis Research, an independent financial research firm, has found. Bear markets accompanied by recessions had a median duration of 528 calendar days and a market decline of 32.8 percent, the firm has found, using Dow Jones industrial average data since 1900. Bear markets that occurred without recessions had a median duration of 224 days and a decline of 23.3 percent.

“Bear markets are unfortunate whenever they occur, but they tend to be much worse if there’s also a recession,” Ed Clissold, chief U.S. strategist at Ned Davis Research, said in an interview.

Yet the Trump tariffs, which would be the steepest in a century if fully carried out, have already set off a global trade war. The president could reverse himself, remove most of the tariffs and try to undo some of the damage, but there are no signs that he’s planning to do so. In the meantime, the chances of a recession and of further market declines have been growing.

Mr. Yardeni said that while he remained optimistic about the long-term prospects for the United States, fear, confusion and uncertainty over President Trump’s tariff policy make him less positive about the next year. The chances of “stagflation” — a dreaded combination of high inflation and a slowing economy — are now 45 percent in the next 12 months, up from 35 percent one month ago, he said, and that wouldn’t help the stock market.

Goldman Sachs says there’s now a 35 percent chance of a recession in the next year, and late in March it ratcheted down its estimate for the S&P 500, projecting a 5 percent price decline over the next three months. At the start of the year, Goldman was rampantly bullish, forecasting a 16 percent increase in the S&P 500 over the course of 2025. If the market falls much further, Goldman and other market strategists are likely to revise their estimates still lower. JPMorgan has already raised the odds of a global recession this year to 60 percent.

As I’ve pointed out in recent columns, though, bonds have been performing well this year, easing some of the pain for investors, and international stock markets have done better than the U.S. ones, although they, too, have been battered as the reality of a new world of higher tariffs has sunk in. Old-fashioned low-cost diversified investing — I practice it using index funds that track virtually all tradable global markets — has eased some of the pain this year.

But in a full-blown recession and a bear market, few people will be entirely spared. Eventually, markets rebound, and those with long horizons are likely to prosper, regardless of what happens in the next few weeks.

Some market declines are blessedly brief. But in the bear market that started in October 2007, during the great recession of that period, it took more than four years, including dividends, for investors in the S&P 500 to climb back to the peak of their holdings in that index.

Even so, it was worth hanging on, for those who were able to do so.

Since the 2007 market peak, the S&P 500 has had a total return of more than 356 percent, even including the latest market declines. Staying in the market has paid off over the long run, and it’s likely to do so again. But sticking with it, even in times like these, can be tough. You need strength and plenty of patience to be a long-term investor.