The Online Casinos That Can Operate as Long as They Say They Aren’t Actually Casinos

In most states, playing slot machines online for real money is illegal. But a group of companies known as sweepstakes casinos has found a way around the law to let users play classic casino games online.

Their revenues have grown 10-fold in the last five years, and they’re now large enough to feature ads with Ryan Seacrest, Drake and Michael Phelps. Only recently have states like New York and Maryland contemplated restricting them, with billions of tax dollars at stake. But the loophole used by sweepstakes casinos complicates the states’ ability — and desire — to take action.

That loophole? The “no purchase necessary” rule that differentiates a legal sweepstakes from an illegal lottery.

It’s a rule you might be familiar with if you ever played McDonald’s Monopoly promotion. In case you missed it, here’s how it worked: During the promotion, certain menu items came with special “game piece labels” from the Monopoly game board. These could be traded in for prizes, like a free hamburger or a cash sum. The key is you weren’t buying the tokens directly; they came with your purchase of fries. And in order to fully qualify as a sweepstakes, McDonald’s also had to let you receive tokens by mail — where the “no purchase necessary” comes in.

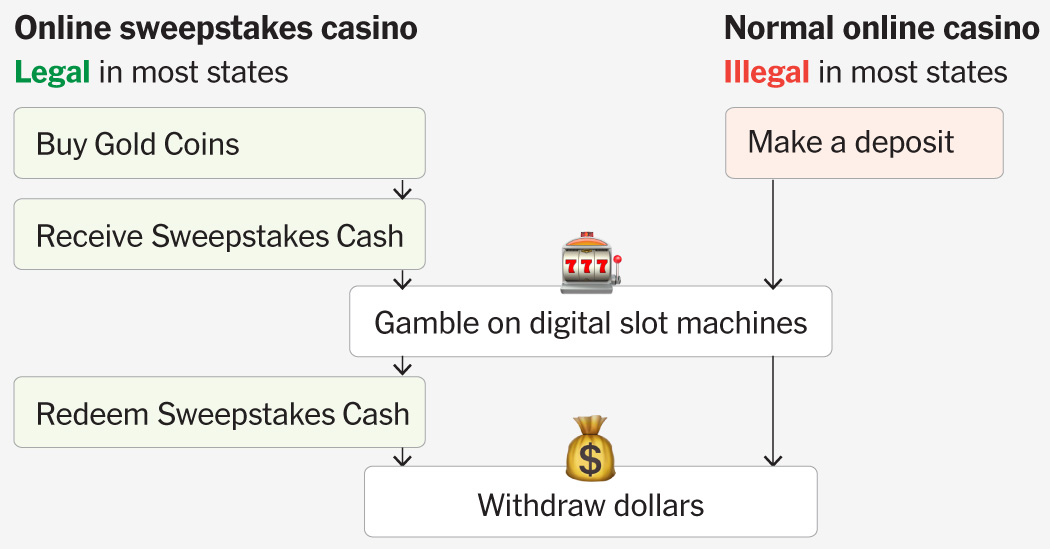

Instead of selling fries, the sweepstakes casinos sell a valueless online currency often called Gold Coins. (You can use the coins as play money for gaming, but they cannot be redeemed for prizes.)

And instead of a Monopoly token, your purchase earns you another currency, often known as Sweepstakes Cash. This “cash” is usually equivalent to dollars. So if you spend $100 on Gold Coins, you receive $100 worth of Sweepstakes Cash. This is what you can then use to gamble on games like blackjack or roulette, cashing out any winnings back into dollars.

You can also receive a small amount of Sweepstakes Cash free by mail, mirroring the same sweepstakes rules that a promotion from McDonald’s would follow. By adding extra layers to the process, the sweepstakes casinos have, in practice, made it possible to gamble legally online in states that otherwise ban online gambling.

There’s a lot of demand for it. Sweepstakes casinos first appeared in 2016 and have grown exponentially to an estimated $8 billion in yearly revenue.

Drake University law school professor Keith Miller compared sweepstakes casinos to other companies that grew rapidly while operating in legal gray areas: “It’s like what Uber did. They just said what we’re doing is completely legal and we don’t need to be regulated.”

There is at least one major sweepstakes casino currently operating in 47 states. Most states have not taken action, but since 2024 lawmakers in at least 10 states have introduced legislation to close the legal distinction that sweepstakes casinos use to operate.

In an email, Ryan Bailey of the Social & Promotional Games Association said it was a misconception that sweepstakes casinos are “rebranded online casinos”; instead, they use a different model that “allows for free entry and is built around promotional engagement, not gambling.”

Playing Whac-a-Mole

In New York, where state law prohibits online casino gaming, State Senator Joseph Addabbo Jr. recently introduced a bill to ban sweepstakes casinos. “We’re not talking about hamburgers,” he said. “We are talking about online gambling.”

But legislation has challenges. Even though Mr. Addabbo Jr. is the sponsor of the bill, he said the legislative process would be a “cumbersome and slow way of dealing with it.” He stated it would be “more efficient” if the state gaming commission or state attorney general stepped in instead.

Regulators don’t have perfect enforcement options, either. Sweepstakes casinos have no gaming license to revoke. And if a state attorney general made a case they were operating illegally, sweepstakes casinos could claim they were operating by the same rules as all other legal sweepstakes.

John Holden, a professor at Indiana University who has written extensively on the history of gambling regulation, compared the current situation to “playing Whac-a-Mole.”

“Say you crafted a new law that targets these sweepstakes casinos,” he said. “What if someone comes up with something new? I think that’s driving a lot of hesitation for legislators.”

Sweepstakes casinos are not unique in testing the limits of gambling laws.

Most states restrict slot machines but allow for prizes to be won in “games of skill,” like throwing a basketball into a hoop at a state fair. In Pennsylvania, many gas stations now have games called “skill-based slot machines.” In most ways, they are like any other slot machine, but with an added “skill” element, like making the user click a matching symbol to win money.

A share of the pot

Lawmakers in most states have not been active in chasing after sweepstakes casinos.

“If I pass a law, I want it to have impact; in order to have impact, it needs to have enforcement,” Professor Holden said of the calculus facing lawmakers. “New resources have to go into enforcement, and it’s sort of difficult in my mind to see that having a big return.”

It might seem that states with strict anti-gambling laws would be the most aggressive about reining in sweepstakes casinos. The opposite is true; it’s states with legal online gambling that have more incentive to ban sweepstakes casinos.

Sweepstakes casinos pay no gambling tax — thanks to the loophole they use to avoid being classified as gambling. For states that ban online gambling, there’s no lost revenue.

New Jersey, Connecticut and Maryland allow online casino gambling. This year, all three have had state lawmakers introduce laws banning sweepstakes casinos.

In 2019, when Michigan passed a law legalizing online casino gaming, the Michigan Gaming Control Board also gained the power to investigate any site offering gambling without a license. In 2023, the state shut down a sweepstakes casino that was still accepting customers in Michigan.

Kurt Steinkamp, chief of staff of the Michigan board, says its license system helps ensure fairness and compliance with consumer protection regulations. It also ensures that when residents gamble online in Michigan, the state sees its share of the revenue.

“Companies that operate either in the black market or in the gray market are directly competing for revenue with licensed regulated entities,” Mr. Steinkamp said. “And that certainly impacts tax dollars.”

Online casino gambling in Michigan is big business. In 2024, the state gained about $450 million in tax revenue, compared with $147 million collected from online sports gambling. That relationship is true in almost all states that allow both types of gambling.

Some state lawmakers have found it more compelling to legalize and regulate online gambling than to try to eliminate all forms of online gambling. Lawmakers in Arkansas last week introduced legislation to legalize online casino games while also banning sweepstakes casinos.

As for the sweepstakes casinos, in order to keep growing, they’ll need most states not to follow Arkansas or New York, but to stay right where they are.

Additional work by Alicia Parlapiano