Today is Trump’s ‘Liberation Day.’ What does that mean for tariffs?

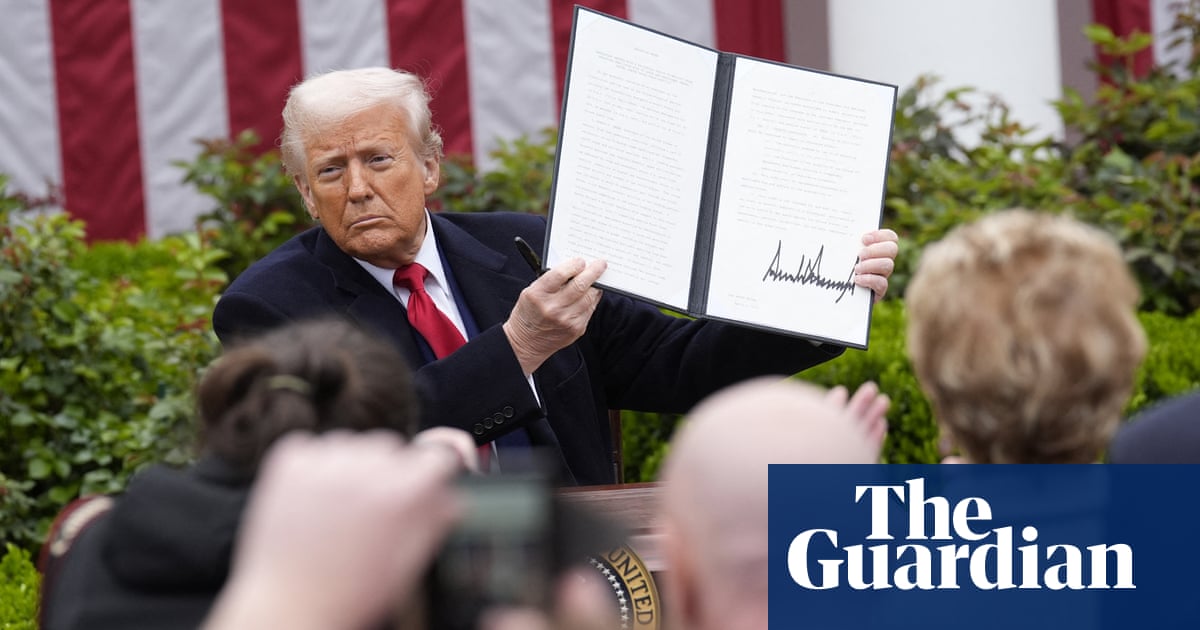

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt holds up a chart showing tariffs on American goods as she speaks with reporters at the White House on March 31, 2025.

Saul Loeb/AFP

hide caption

toggle caption

Saul Loeb/AFP

On Wednesday, President Trump is set to unveil what he has been calling “reciprocal tariffs” — taxes on imported goods from a broad range of countries aimed at penalizing them for their trade barriers.

It’s a push he is branding as “Liberation Day,” promising it will bring in foreign tariff revenues to be put toward U.S. tax cuts and deficit reduction, and spur a renaissance in U.S. manufacturing.

But the pledge has glossed over the pain expected to be felt by U.S. consumers who economists expect will end up paying higher prices — and by U.S. farmers and exporters targeted for retaliation by other countries.

Some U.S. manufacturers will be hurt by higher costs for imported materials. And mainstream economists are skeptical that the tariffs will bring in as much revenue as Trump has promised.

While details on his plans are sketchy, the Yale Budget Lab estimated the scheme could cost the average American consumer $2,700-$3,400 per year.

The uncertainty over the policy has roiled the economy. The S&P 500 stock index just closed out its worst quarter since 2022, and consumer confidence recently hit a 12-year low.

Trump had vowed that the tariffs will mirror what other countries impose on U.S. goods. But lately, he has appeared to moderate his tone.

“They took advantage of us,” Trump told reporters on Monday. “And we are going to be very nice by comparison to what they were. The numbers will be lower than what they’ve been charging us and, in some cases, maybe substantially lower.”

The Canadian government has placed anti-tariff billboards in numerous American cities, including this one in Miramar, Fla.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Few details about what countries, what products will be hit

Trump’s economic policy has been unique not only in his aggressive rhetoric around tariffs but also in the vagueness and unpredictability surrounding his policy announcements.

Thus far, he has imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum, Chinese goods, and some goods from Mexico and Canada. But he has also threatened, delayed, or withdrawn tariffs on an array of other goods, often telegraphing new potential moves while providing few to no details.

The reciprocal tariffs are another example in this pattern. A February 13 memo laid out the start of the process, instructing Cabinet members and advisers to study how “non-reciprocal” trade relationships might be harming the U.S. economy, then submit reports that propose ways to make trade with any given country “reciprocal.”

At the time, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said those studies would be done by April 1. “We will hand the president the opportunity to start on April 2, if he wants,” Lutnick said.

That still leaves flexibility in the timing of imposing the tariffs. While it’s not clear when specific tariffs will come into effect, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said on Tuesday that they would be imposed “immediately.”

Traders work on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on March 28, 2025. President Trump’s escalating tariff threats have hit stock prices hard.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Trump’s tone on tariffs has softened recently

The White House has not given any details on which countries Trump plans to tariff first. However, while speaking to reporters this week, Leavitt may have provided some clues, holding up a chart showing steep tariffs that Japan, Mexico, Canada, and the European Union impose on certain American goods.

Trump also has said at times that the tariffs will take into account “non-tariff barriers” like subsidies and regulations. But he hasn’t mentioned that lately.

“In fact, I’ll probably be more lenient than reciprocal because if I was reciprocal, that would be — that would be very tough for people,” Trump said in an interview last week with Newsmax.

Trump has left the door open to negotiations, though he has insisted he wants “not too many” exemptions from the reciprocal tariffs.

Will the tariffs be broad or targeted?

A more conventional approach to pressuring other countries to lower their tariffs might be to specifically target a country or a good, said Doug Irwin, professor of economics at Dartmouth College.

“What’s less normal is when you have a much more vague objective, a broad-brush approach to many countries, many possible sectors,” he said. “Things are unfair in different ways with different countries. And it’s very hard to have a uniform, blanket approach to all of that.”

John Veroneau, a deputy U.S. Trade Representative in the George W. Bush administration, agreed that targeted tariffs are more effective.

“There are some unfair trade practices out there. So to the extent that you threaten tariffs … that would call for a very surgical approach,” Veroneau said. “These tariffs presumably will far exceed the number of U.S. exporters that are complaining to this administration or previous administrations about very specific trade barriers.”

Veroneau added that this is symptomatic of a bigger problem with how Trump talks about tariffs as a solution to a wide range of policy problems, some of which conflict with each other.

“The problem that I think surrounds so many of Trump’s commentary and comments about tariffs is, what is the goal of the tariff?” he said.