Trump says his tariffs are ‘reciprocal.’ Are they?

As with many of his political positions, President Trump’s extraordinary new tariffs are based on the presumption that the United States is being treated unfairly by the rest of the world.

He proclaims his tariffs are merely “reciprocal.” “They do it to us, and we do it to them,” Trump said. “Very simple.”

But are the new levies on foreign goods sold in the U.S. truly “reciprocal”?

No, not by any commonly agreed definition of the term.

“A ‘reciprocal’ tariff is one that is equal to the tariff rate charged on our exports to them,” Brad DeLong, a professor of economics at UC Berkeley, said via email. “Vietnam’s tariff on our exports . . . averages 10%. That is not the 46% rate that Trump has imposed” on Vietnam.

The Trump administration tariffs are not even based on the tariffs other countries impose. Instead, they are derived using a novel calculation that focuses on America’s trade deficits with other nations. And the levies Trump said he intends to impose on goods will often be much higher than the ones they charge on American imports.

Here’s how the Trump administration calculated the new tariffs: It took the U.S. trade deficit with individual trading partners, then divided it by U.S. imports from that partner. It then divided that total in half. Thus, Trump claims that his tariffs are not only reciprocal but “discounted.”

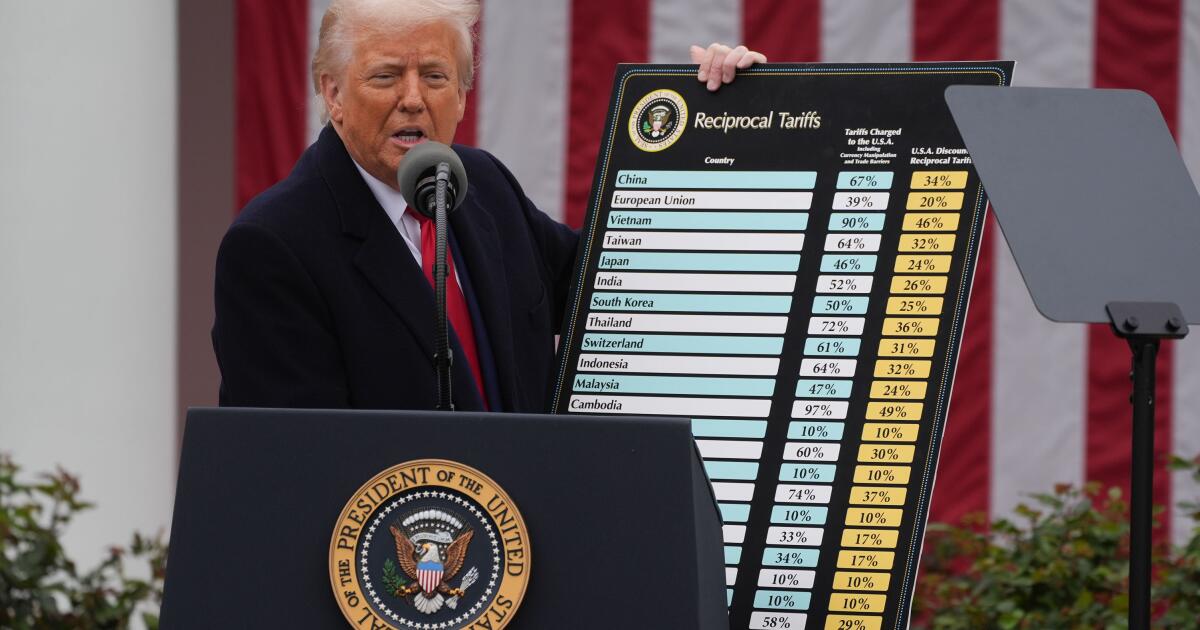

Trump’s acknowledgment that the calculations were not based on other nations’ tariffs alone is demonstrated in one of his social media posts. A chart laying out the new tariffs contends the charges by other nations include “currency manipulation and trade barriers.” To Trump, the new duties are “reciprocal” because they respond to another country’s actions, even if the new U.S. tariffs are much higher.

What the post does not acknowledge is that a substantial portion of the advantage other nations have in trade is tied to lower operating costs, particularly the lower wages and benefits that their workers earn, which are unrelated to tariffs.

Trump Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick insisted that the charges will pay dividends in the long run, as foreign companies — stung by the tariffs — decide to move their factories to the U.S. “Global governments have backed taking our factories away from us,” Lutnick told Newsmax. “But what you’re going to see is the most modern factories of the world come back here.”

Trump has insisted that by effectively raising taxes on imports from other countries, he will help drive down America’s trade deficit. Most economists polled on that notion aren’t buying it.

Fifty-eight percent of the economists surveyed by the Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets at the University of Chicago disagreed with the claim that America’s trade deficit would grow smaller because of the higher tariffs. Forty-one percent said they were unsure. Only 1% of economists said they thought the Trump move would improve America’s balance of trade.

Trump’s view of international trade is also overly simplistic in that it attends only to the material goods the U.S. sells overseas and how much other nations sell in the U.S. without accounting for professional services that America sells in other countries, said Jesse Rothstein, another UC Berkeley economist.

“With many of these countries, and generally with the world, we have a trade surplus when it comes to services,” Rothstein said. “So they send us cheap clothing and we send them accounting services. It’s a good deal. We would much rather be getting paid as accountants than getting paid as garment workers.”